|

|

Post by Aurelia on Mar 27, 2020 11:33:01 GMT -5

Since I'm essentially on lock down in my home, I've been toying with the idea of making fully boned stays for some of my 18th century costumes... the project is rather time and labor intense, but as there's no where to go at the moment, it seems as good a time as any! While I procure my boning (through some non-contact means), I figured I'd write a bit about the history of corsetry... Though, I have to say from the start here, I refuse to follow the more modern narrative of "corset as torture implement" that seems to be impossible to separate from the history of this fashionable piece. Anymore it seems that the corset has become a symbol of either male oppression or female suffering and subjugation, which seems quite a heavily loaded interpretation for supportive garment. **Nota Bene... this write up will be posted section by section, as I'm afraid of loosing my work / links! **  A quick glossary...Corsetieres or Corset A quick glossary...Corsetieres or Corset : this term is incorrectly used for any sort of historical shaping undergarment. This refers more specifically to the body shaping undergarments seen after the 1800's. They were more funnel-shaped, and as the century wore on, encouraged a sort of "pigeon" shape to the chest. "Payre of Bodies", Bodies or Bodice : seen during the Elizabethan era, worn over the chemise, functioning as a visible part of a woman's attire. Elizabeth I's "effigy corset" remains as an example. "Pair of Stays" or Stays : this terms indicates the body shaping undergarments seen during the 1700's. They created a cone-like shape, pressing the breasts up and tapering at the waist. Busk : a large section of whale bone or wood that was incorporated into the front of stays and corsets to maintain a straight shape. There were one and two piece busks; two piece would include a series of clasps and one piece busks would be slide down along the sternum into a elongated pocket. Stomacher : a triangular piece of fabric that covers the front of a bodice - it may be boned as part of the bodice or simply used as a decorative covering to hide the front lacing. Jumps : a soft, fabric vest - without boning - used to support the figure (often worn at home). Jumps were considered to be the less formal, but more comfortable alternative to stays. The Catherine de Medici MythWhile there is evidence that the corset existed since ancient times (the Heraklion Snake Goddess example from c. 1600 BC), it was Catherine de Medici that will forever shoulder the blame in the "modern" history of the restrictive undergarment.  People widely cite Catherine de Medici with the cruel introduction of rather extreme looking metal corsetieres into fashion - but in retrospect it seems that these metal corsets were the work of French army surgeon, Ambroise Paré, who created the object in the 16th century to treat "crookednesse" of the body in patients suffering from orthopedic complaints. 1 It is far more likely that the stiffening of garments and shaping of the female figure was initially created through a much gentler means: with the incorporation of buckram - a cotton cloth made rigid with starches and glues - to stiffen the cloth. Many of Holbein the Younger's sketches from 1520 and portraits from 1530 show these buckram stiffened kirtles, where the stomach and chest are one smooth plane. Later a lattice of reeds and whalebone (baleen) were employed to accomplish the task of stiffening the garment. Whale baleen would become so intrinsically linked to the manufacture of corsetry, that the garment was known as corps à la baleine to the French . Elizabeth I's wardrobe inventories mentions several pairs of bodies using several different methods of stiffening: The ultimate goal of the pair of bodies was not to draw in the waist for a tiny midriff - which is a more modern paradigm of feminine beauty - but to smooth the torso into a cylindrical shape, and raise the bust line dramatically.  Portrait of Jane Seymour by Holbein c 1536 - showing a silver embroidered, stiff buckram-backed kirtle giving shape to the red velvet gown layered over it. Portrait of Jane Seymour by Holbein c 1536 - showing a silver embroidered, stiff buckram-backed kirtle giving shape to the red velvet gown layered over it. Portrait of Elizabeth Vernon c. 1600 - shown wearing a pair of bodies - stiffened with bone. Portrait of Elizabeth Vernon c. 1600 - shown wearing a pair of bodies - stiffened with bone.  The "Effigy Bodies" of Elizabeth I - fully boned The "Effigy Bodies" of Elizabeth I - fully boned

More in a bit....

Sources: 1 The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey By Ambroise Paré

2 Arnold, Janet. (1st edition) (2019) Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlock'd. Routledge. |

|

|

|

Post by Aurelia on Mar 28, 2020 11:21:06 GMT -5

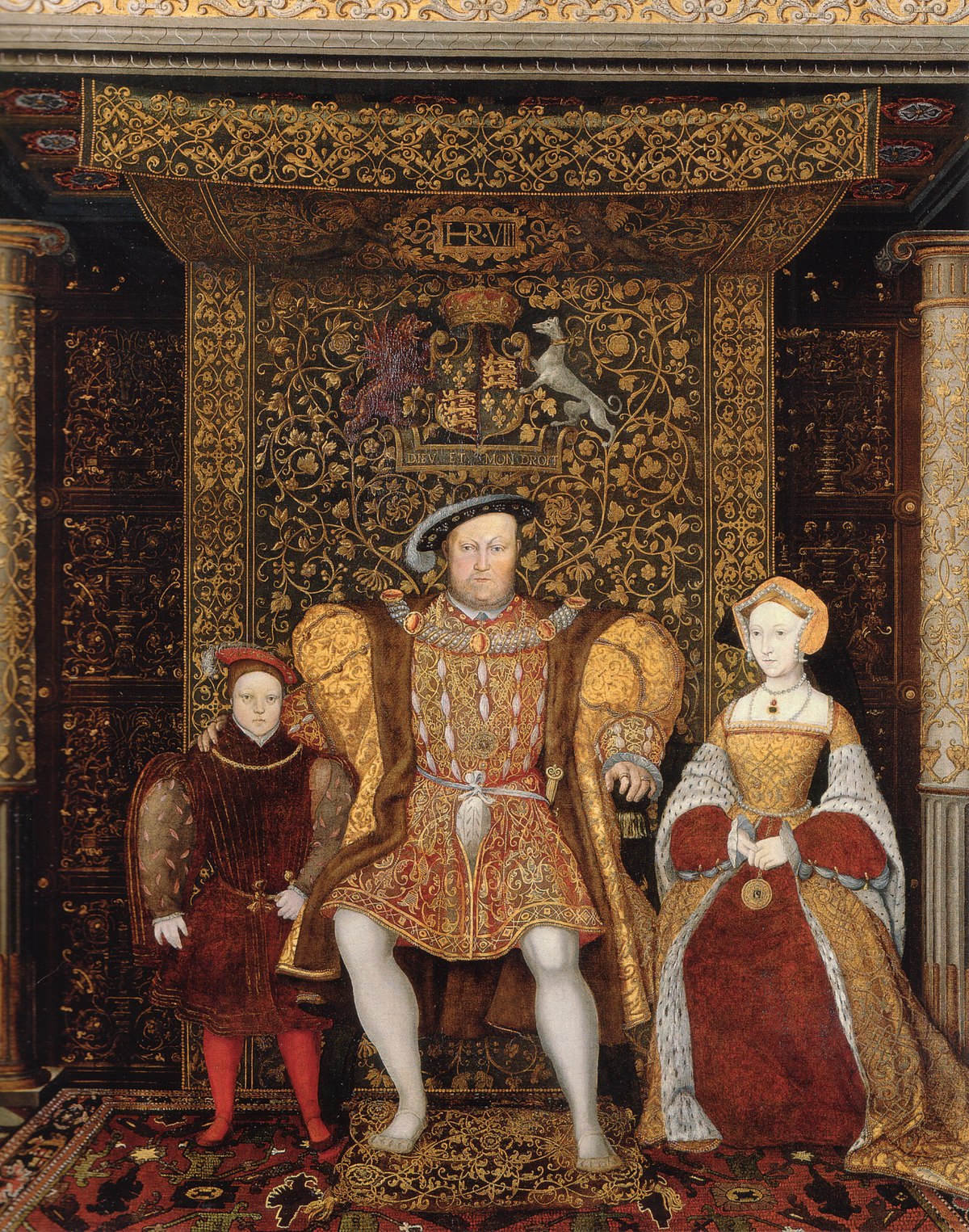

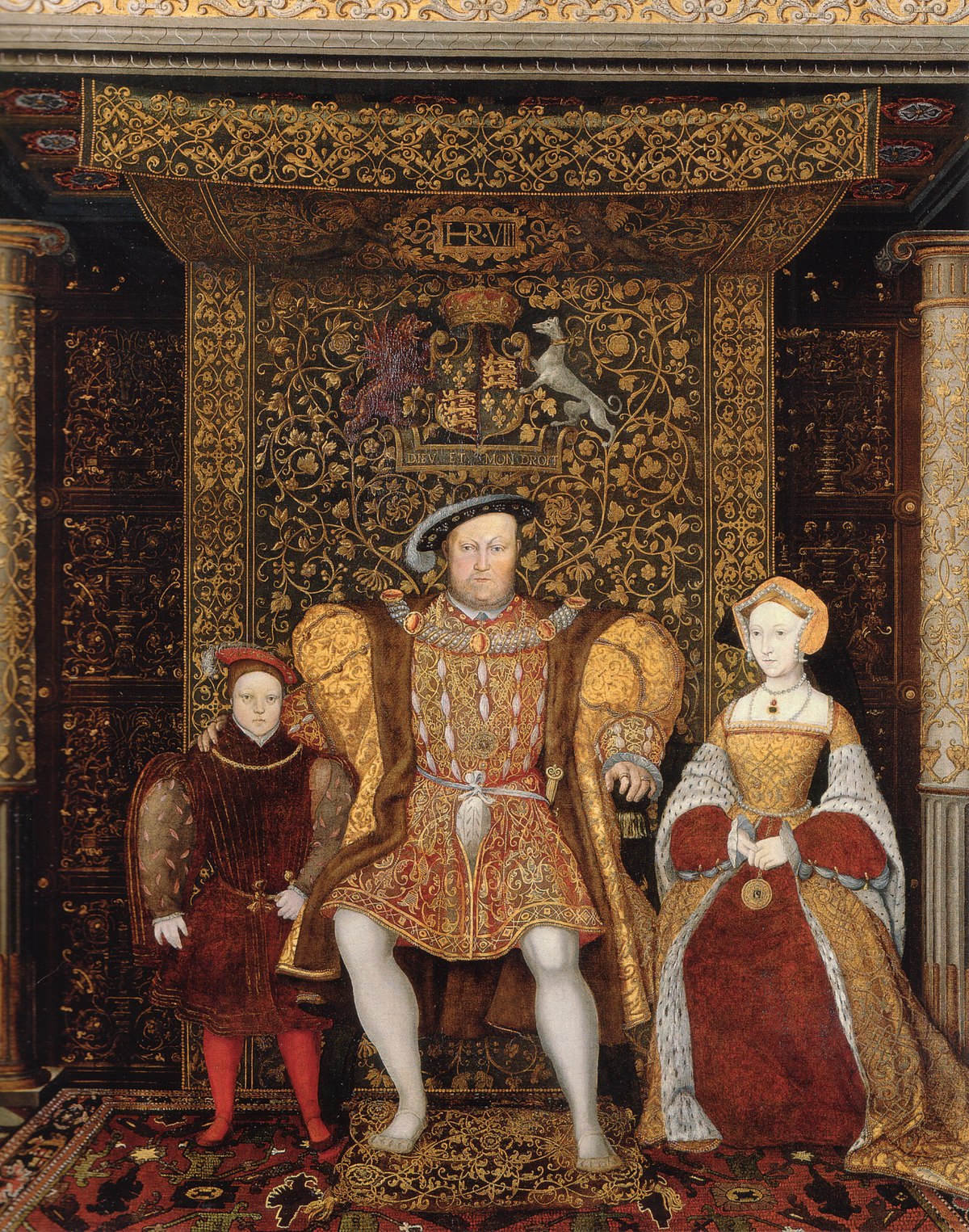

Transition From Outer Garment to Under GarmentThe kirtle, which had initially been loose fitting garments with no waist seam, would slowly perform a sort of fashionable disappearing act as the years passed. It transitioned into a highly form-fitting, supportive garment in the late 14th century, reinforced with a number of different elements such as buckram, baleen, whalebone, wood, horn and reed. As fashion shifted towards wearing layered gowns over a kirtle, the piece began to be buried under layers of dress, but it was wisely retained as an shaping undergarment. There was a practical element involved here, as it was far simpler to have one single, stiffened undergarment to be worn under many gowns than to stiffen each gown itself - it also reduced the wear on outer garments to have one piece worn close to the body, creating shape while absorbing perspiration that soaked through the chemise. After 1545, the kirtle would have been attached to a stiffened pair of bodies and any parts of the kirtle skirt or sleeves that would be visible under the gown would be ornamented with richer fabric accents.  Jane Seymour wearing a decorative red kirtle under a dress covered with elaborate, gold embroidery - c 1545 unknown artistIntroduction of the Busk Jane Seymour wearing a decorative red kirtle under a dress covered with elaborate, gold embroidery - c 1545 unknown artistIntroduction of the Busk

The broader conical silhouette with higher waistline of the 1530's gave way to an exaggeratedly long, stiffened, V shaped waist. In order to support the garment and maintain a flawlessly smooth and upright torso, the introduction of a busk was necessary. Usually carved from wood, ivory or whalebone (a term often used for baleen), a one- piece busk would slide into a specially designed pocket that ran along the sternum and down to the pubic bone.  Corset of Dorothea von Neuburg from 1598 with visible pocket for busk Corset of Dorothea von Neuburg from 1598 with visible pocket for busk

Modern reproduction of a historical corset showing pocket for busk

English clothing historian, Janet Arnold, collected references from clothing warrants in her book, Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlock'd, including one that details the inclusion of a whalebone busk: Busks were often given as a gift from men to their sweethearts and inscribed with a variety of symbols and messages to the wearer. Many examples still exist, showcasing the decorative quality of what would seem to be highly intimate gifts. An inscription on a decorated, metal busk given to Anne-Marie-Louise d’Orleans, Dutchess de Montpensier, reads:  Love token busk from c. 1850 Love token busk from c. 1850

'We Are One' inscription on a busk gifted from a British-held American prisoner to his wife - 1782

Sources: 3. Arnold, Janet. (1st edition) (2019) Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlock'd. Routledge. 4. Mirabella, Bella. (4th edition) (2014) Ornamentalism: the Art of Renaissance Accessories. University of Michigan.

|

|

|

|

Post by The Duchess on Mar 28, 2020 20:08:55 GMT -5

Quality thread, Aurelia! I look forward to reading more of your work.

|

|

|

|

Post by Aurelia on Mar 29, 2020 12:54:28 GMT -5

A Shift From Form-Blurring to Form-Enhancing

It must noted that up until the 17th century, the purpose of wearing buckram backed bodices and whalebone reinforced 'payres of bodies' was to smooth the curves of the female figure, creating a shape that in many ways resembled a more androgynous, powerful appearance. When comparing images of men and women from the Elizabethan period, the similarities in appearance between a cuirass (French corselet) and a pair of bodies are striking - and commented on by contemporaries:  Elizabeth I - 'The Ermine Portrait' Elizabeth I - 'The Ermine Portrait'

Portrait of Walter Devereux (1539–1576), First Earl of Essex Portrait of Walter Devereux (1539–1576), First Earl of Essex

As the styles changed in the mid 1600's, there was a very dramatic shift towards supportive garments being employed to enhance the female form rather than obscure it. As dramatic ruffs and ornate colors fell from vogue, necklines plunged to reveal the topmost curve of the breasts - bodices were cut back to bare the tops of the shoulders. The tube-like shape of the torso remained, with an slight concavity to the stomach and ending in a very emphasized, sharp V far below the natural waistline.  Portrait of Maria Louisa de Tassis by Anthony Van Dyck. C. 1629. Portrait of Maria Louisa de Tassis by Anthony Van Dyck. C. 1629.  The Silver Tissue Dress - 1660 - note low, round neckline revealing decolletage and shoulders - as well as ruffled white chemise.The Romantic Negligence of 'Undress' The Silver Tissue Dress - 1660 - note low, round neckline revealing decolletage and shoulders - as well as ruffled white chemise.The Romantic Negligence of 'Undress'

The state of undress ( déshabillé) in the past referred to any attire other than court dress - it was usually more comfortable, everyday wear. In the 1680's, it had become fashionable to wear what was described as déshabillé négligée for rather provocative portraiture. The informal "night gown" (also called day gown, Indian night gown) was a loose fitting dress that was worn over the chemise (tantamount to underwear) with a draped mantua about the shoulders. This fashion became the rage for both men and women, but in looking at the images of the style, the question comes to mind: where these women wearing any supportive undergarments? Or were they "loose women" - a phrase that referred to their lack of stays and lack of morals as being two sides of the same coin.  Portrait of Mary ‘Moll’ Davis by Lely. C. 1665-1670. Looking rather unsupported! Portrait of Mary ‘Moll’ Davis by Lely. C. 1665-1670. Looking rather unsupported!

Barbara Villiers (1640–1709), Countess of Castlemaine and Duchess of Cleveland by Lely. C 1662. Barbara Villiers (1640–1709), Countess of Castlemaine and Duchess of Cleveland by Lely. C 1662.

The smoothness of the torso in the example image of Barbara Villiers would indicate there was some stiffening garment in use - but was it the bodice, kirtle, petticoat or stand alone pair of stays? It's difficult to tell - and as the styles changed, the method of which was reinforced tended to shift - until the early 1700's as the bodies slowly transformed from an outer garment to undergarment, known as stays ( estayer). 5. Gosson, Stephen, 1554-1624, and Edwin Johnston Howard. Pleasant Quippes for Upstart Newfangled Gentlewomen. Oxford, O.: The Anchor press, 1942. |

|

|

|

Post by The Duchess on Mar 29, 2020 13:48:25 GMT -5

I really enjoyed the last installment! The trend of déshabillé in Restoration portraiture seems to be incredibly indicative/representative of the era. The "loose" women parallel is quite interesting, and I think it merits more investigation. If it doesn't derail your thread too much, I'd like to supply a few other images of déshabillé.

(Catherine Sedley, mistress to James, Duke of York. Notice not only that her dress is undone in the front and the chemise nearly slipped from her shoulders, but that she is holding back bed curtains!)

(Pretty, witty Nell. One of Charles II's most famous mistresses, and a virtual folk heroine.)

(Louise de Kerouaille, Duchess of Portsmouth. Another one of Charles' main mistresses, and the constant thorn in Nell's side, it seems.)

There's a great collection of déshabillé portraits to be found in Sir Peter Lely's very much erotic Windsor Beauties collection, which was done during the 1660s. Compare that to the more formal, restrained, and moralistic portraits found in Kneller's Hampton Court Beauties, which was painted some 30 years after Lely's series. The decadence is seriously dialed down, and I think it not only conveys changes in fashion, but also, changes in how people were expected to conduct themselves and behave. Gentlemen getting riotously drunk, vomiting into a potted plant and then killing someone with their rapier for looking at them wrong may have been permissible in the 1660s, but more was expected of the post-Restoration man. It seems that the social mores of the men were not the only thing expected to change. The sexual nature of the Windsor beauties -- opened bodices, bedroom eyes, lounging postures -- is corrected by the more formally poised, regal, elegant Hampton Court beauties. Do you think that we can read social and political history from the history of fashion, or is this a bit of a stretch? It may also be due to the nature of the monarch. I doubt that Charles II would have minded the female courtiers walking about in states of undress, but later monarchs would be agog and disgusted at such impropriety.

|

|

|

|

Post by Aurelia on Mar 30, 2020 13:55:36 GMT -5

There's a great collection of déshabillé portraits to be found in Sir Peter Lely's very much erotic Windsor Beauties collection, which was done during the 1660s. Compare that to the more formal, restrained, and moralistic portraits found in Kneller's Hampton Court Beauties, which was painted some 30 years after Lely's series. The decadence is seriously dialed down, and I think it not only conveys changes in fashion, but also, changes in how people were expected to conduct themselves and behave. Gentlemen getting riotously drunk, vomiting into a potted plant and then killing someone with their rapier for looking at them wrong may have been permissible in the 1660s, but more was expected of the post-Restoration man. It seems that the social mores of the men were not the only thing expected to change. The sexual nature of the Windsor beauties -- opened bodices, bedroom eyes, lounging postures -- is corrected by the more formally poised, regal, elegant Hampton Court beauties. Do you think that we can read social and political history from the history of fashion, or is this a bit of a stretch? It may also be due to the nature of the monarch. I doubt that Charles II would have minded the female courtiers walking about in states of undress, but later monarchs would be agog and disgusted at such impropriety.

Thanks for sharing those additional déshabillé images - they are perfect examples of the trend for these un-bodiced, casual (though highly sensual) portraits being made at that time! I definitely think that some of the messages in these images (the motivations behind them and the sociological structures that allowed them) are about political and religious shifts happening at the time, as well as social mores being used to convey specific meanings. From what I understand of the era, it was a time where modern philosophy was just beginning to emerge - and philosophy was finally starting to separate from religion. As you move towards the Age of Enlightenment, you can see how the humanistic influences that reemerged in the Renaissance fed into how artists and thinkers interpreted the world around them. Many of those same visual cues are incorporated into these portraits - the "classical" sort of drapery, the hair styling, etc. These sorts of insouciant portraits were also made of men (who would wear decorative banyans, which were essentially a dressing gown) during that time... it had become quite stylish to be in a state of undress. Some writers said that it was a refreshing break from the extremes of "full dress" required in court - that is was less affectatious and conveyed a more genuine sense of the individual. It's also important to note, that during this era, only people of higher social status could receive a person while in a state of undress. Anyone of lower status still had to appear 'dressed', all the way down to their hat and gloves. These images of the sitters in a state of undress conveyed power and status to whoever happened to view them, so while they seem very coy and sensual, there was also this message of social status being conveyed. So there's sex and power mixed in there... quite an intoxicating combination! |

|

|

|

Post by The Duchess on Mar 30, 2020 14:28:00 GMT -5

It's also important to note, that during this era, only people of higher social status could receive a person while in a state of undress. Anyone of lower status still had to appear 'dressed', all the way down to their hat and gloves. These images of the sitters in a state of undress conveyed power and status to whoever happened to view them, so while they seem very coy and sensual, there was also this message of social status being conveyed. So there's sex and power mixed in there... quite an intoxicating combination! (Emphasis mine.)

Hats are very important! King Charles II, for instance, had a habit of receiving people with his hat in hand, sitting down (wig still on, of course). His brother, King James VII/II, however, always kept his hat firmly on his head, and stood up for the entirety of the meeting. I feel like that sort of thing reveals a lot not only about the individual king's personality, but also, their ideas about politics.

|

|

|

|

Post by Aurelia on May 12, 2020 14:37:18 GMT -5

(I got a bit distracted here... my modern "whale bone" was delivered and I started making a pattern for my stays project) A Return to Stays in the 18th CenturyAt the turn of the century, the idealized lines of women's fashion took a turn away from looking "undone" and moved towards an angular shape with lengthened waist and very straight posture. The straps that had receded to just off-shoulder in the late 1600's returned to the tops of the shoulder - after 1750, the straps would disappear completely. The most fashionable stays forced the shoulders back to where the shoulder blades nearly touched. This silhouette - very upright posture, open chested, conical shaped torso with shoulders thrown back - is completely unique to the early part of the 1700's. To enhance the hips, tabs were cut along the bottom of the corset, making the boning flare out and create the optical illusion of a smaller waist. Even with the alterations being made in posture, the stays were not laced particularly tight and would only alter the wearer's overall proportion by and inch or two. It was all about enhancement - still no augmentation like would be seen later. There were two different methods of construction for stays at this time: "fully boned" which were lined with whalebone, reed or steel from front to back; and "half boned" which used less stiffening and had more areas that were just fabric. To achieve the flawless cone-like shape that was so desirable, boning was often arranged at different angles to strategically reshape the body.  Fully-boned stays from the late 1700's. European. Brown cotton cover and lining. Fully-boned stays from the late 1700's. European. Brown cotton cover and lining.    Half-boned stays - also late 1700's. Damask silk lined with linen.The Everyday Alternative : Jumps Half-boned stays - also late 1700's. Damask silk lined with linen.The Everyday Alternative : Jumps

During the 1700's, there were no hard and fast rules for wearing shaping undergarments: they were largely regulated to certain socioeconomic groups, unlike the 1800's, where the corset would be worn by all social classes. It was noted that stays were more popular in England than France, where even the working classes would be seen wearing them. Even the poorest women would have a pair of second or homemade stays and a petticoat as the bare minimum for decency. Visual and textual evidence even suggests that rural working women, such as sheep shearers and gleaners were wearing their stays over shifts/chemises and petticoats while working. English dress historian, Anne Buck, writes "Women wearing their stays in this way [that is, visibly] felt no more undressed than a man who removed his coat to work." 6During this time, Jumps were seen as a healthier, easier alternative to stays, especially when at home. Jumps aren't much more than a stiffened fabric bodice that laced in the front, making it easy for it's wearer to take on and off without assistance. The term "Jumps" is believed to be derived from the French jupe, which referred to a short jacket - and much like a jacket, they offered minimal shaping with no boning, so the very desirable "cone shaped" figure was lacking. The contemporary attitudes about jumps reflected something akin to the feelings people have today about a pair of old sweatpants: a mixture of comfort and causal wear for everyday with a touch of slovenliness and poor taste. This was a time when women were being hand-stitched into their dresses all to create an impeccable fit - displaying a slack and wrinkled torso was a heinous act outside of one's own home. From the letters of Elizabeth Charlotte, Princess Palantine (sister-in-law to Louis XIV of France) the attitude towards jumps was made quite plain, especially in one passage from a note penned December 14th, 1704: A poem entitled "Fashion and Beauty" from 1762 also pegs the public image of jumps versus stays: Apparently the social pressure to wear stays was enough to cause one young girl - whose mother refused to let her wear stays and insisted she wear jumps - to commit suicide by leaping out a window to her death. A rather gruesome poem was published in newspapers shortly after, immortalizing the affair: 6. Sorge-English, Lynn. (2011). Stays and Body Image in London: The Staymaking Trade, 1680-1810. Pickering & Chatto (Publishers) Limited. 7. Do Rozario, Rebecca-Anne C. (2018). Fashion in the Fairy Tale Tradition: What Cinderella Wore. Springer. 8. Steele, Valerie. (2003). The Corset: A Cultural History. Yale University Press. 9. Steele, Valerie. (2003). The Corset: A Cultural History. Yale University Press. |

|

|

|

Post by Aurelia on Jun 22, 2020 17:41:56 GMT -5

The Robe le Cour and the Impact of the Sun King   Sofia Magdalena’s wedding gown, Robe le Cour. 1766. Sofia Magdalena’s wedding gown, Robe le Cour. 1766.

Upon finishing his royal residence at Versailles, Louis XIV also implemented shifts in courtly dress that would ultimately transcend his desire to showcase his power and influence to the world and usher in the beginning of what we know as "fashion". Louis XIV, despised the loose-fitting, casual mantua that was gaining popularity at the end of the 1600's, and his answer was regulating the clothing of women in his court... you were not allowed to be seen in court without his specially designed Robe le Cour (known as the "Stiff Bodied Gown" to the English). He based the design on the fashions popular during his youth (1660's), with shoulder skimming necklines and heavy boning sewn into the Robe le Cour itself - eliminating the need for stays underneath.   Left: Inside view of Sofia Magdalena’s Robe le Cour's stiffened bodice - Right: Close-up of lacing down the back of the bodice. Left: Inside view of Sofia Magdalena’s Robe le Cour's stiffened bodice - Right: Close-up of lacing down the back of the bodice.

Louis XIV would establish the first dressmakers guild and would establish furniture, textile and jewelry industries in France that would bring work to his people and also establish France's particular tastes and technologies as foremost in Europe. Essentially, Louis would transform craft into fashion - and make a tidy sum exporting it to the rest of the World. Though later Marie Antoinette would remark that the Robe le Cour was a bit fusty and outdated, and she would allow for her ladies to wear the Robe a la Francaise over stays. The Robe le Cour remained as the height of propriety (and the most acceptable mode of dress for the French court functions) up to the Revolution.  A lady showing a miniature bracelet to her suitor, Jean-Francois de Troy. c. 1734 A lady showing a miniature bracelet to her suitor, Jean-Francois de Troy. c. 1734

Throughout the 1600 and 1700's, fabrics used to make stays would encompass a beautiful range of colors and patterns - with decorative, contrasting ribbon trims used as edging for tabs and straps. The undergarments of these years were as elaborate as many dresses worn over them - with the interchangeable quality of some pieces being worn both under clothing or as a top layer itself, there was good reason for stays to be decorative and beautiful. It was only well into the 1800's that stays would adopt a very clinical, standard white shade, as they were regulated to the status of "unmentionables" and hidden from sight.  Silk, baleen. Spanish. Early 18th C.  Green silk damask, embroidery, baleen. European. Third quarter of 18th century.  Silk, linen, leather, wood, baleen. French. Late 1760's.  Silk Brocade. c. 1750-1760's.  Silk, metallic thread. French. Late 17th–early 18th century Fashion and Revolution

With the French Revolution, mode of dress associated with the aristocracy suddenly became a rather dangerous, visible dividing line between the classes. Fashion itself, underwent something of a revolution, as the waist lines rose to just below the breasts with a far more naturalistic silhouette overall. There were no panniers or hoops to broaden the skirts - and the need for maintaining a cone-like, waspy waist grew obsolete as the trend towards allowing fabrics to hug the natural curves of the body dominated.  Ultra-fashionable citizens of Paris wore: "Flesh colored, knit work silk stays, which stuck close to the body [and] did not leave the beholder to divine, but to perceive, every secret charm." 10"THREE petticoats? No one wears more than one! STAYS? Every body has left off even corsets! 11

There were rather influential persons who made no secret of their disapproval of stays. Napoleon Bonaparte was a vocal decrier of the garments, describing them as "the implement of detestable coquetry which not only betrays a frivolous bent but forecasts the decline of humanity". 12

For those women who wanted support, a range of shortened corsets were developed that would be unique to this era in fashion: short stays, bust bodices and demi-corsets. All of these stays were only as long as the ribcage - short stays were lighter and less boned; bust bodices were more like boned proto-brassieres; and demi-corsets were shorter, lightly boned corsets for informal wear.  Silk, metal, baleen. French. c. 1805-1810. 10. Steele, Valerie. (2003). The Corset: A Cultural History. Yale University Press. 11. “The journals and letters of Fanny Burney (Madame D'Arblay), Volume VI, France 1803–1812 Letters 550–631.” Medical History vol. 20,3 (1976): 325. 12. Schwarz, G. S. "Society, physicians, and the corset." Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, Volume 55(6), 1979 Jun, 551–590.

|

|

|

|

Post by Aurelia on Jul 27, 2020 11:55:27 GMT -5

Stays for Men and ChildrenWomen were not the only strata of society wearing stays. Children of both genders born into wealthy families were wearing corsets in an attempt to alter their growing body into a more aesthetically pleasing form for the era. This was especially important for young boys, as the desired figure for an adult male was one with sloped shoulders that would elongate the neck. George Washington wore stays up until about the age of five - as was the cultural norm for boy in the 18th century - this fact was taken into account during the forensic reconstruction of the first President's appearance as a young man. 13     Child's Stays. 1760-1790. Child's Stays. 1760-1790.

The stays were used to gently mold the growing body, pressing the shoulders down and the ribs inward - similar to the idea of foot binding in Eastern cultures. When a boy was breeched, he gave up the stays and was dressed like a miniature adult. It makes one wonder if those striking silhouettes of men in the 1700's were entirely fabricated from the cut of their clothes - or perhaps helped by the altering of bone development in childhood stays - and later the use of corsets. ![]()  Portrait of Two Children. Antoine Pesne. c.1730. Men's corsets - which would be perhaps described as a girdle in some cases, as it only altered the shape of the stomach and back - were a common wardrobe necessity for men of the 18th and 19th centuries. It was during the Rococo period that men were using false calves to pad their legs for a desirable "S" curve, donning elaborate wigs and dipping into cosmetics in an attempt to present a flawless appearance to the public eye. The demanding close cuts of men's wear required a bit of physical augmentation - most often around the waist.  A satirical image of a dandy being laced in his corset, and padded out through the shoulders, hips and calves. A satirical image of a dandy being laced in his corset, and padded out through the shoulders, hips and calves.

During the transition away from longer, looser cuts of waistcoats to the shorter, form fitting waistcoat of the 1700's that rose high enough to reveal the tops of the breeches, there became fewer and fewer opportunities to hide figure flaws. The trend for body hugging waistlines on men continued into the Victorian era. Popular male shaping garments were sold as "The Brummel Bodice", which was essentially a corset sewn into and hidden by a waistcoat - this design was also marketed under the more masculine nomenclature of "The Cumberland Corset" or "The Apollo Corset".  Men's corset (note the lack of support for the breasts). 1810-1850. American or European. Men's corset (note the lack of support for the breasts). 1810-1850. American or European.

While examples of men's corsets rarely survived to the modern day, there are a few key garments worn by the most influential men of the day - and copious cultural evidences of the commonplace use of corsets for men. One such item is housed in the Museum of London: a corset that had belonged to King George IV, who sported an alarmingly massive (size 50) waist. Fashioned with whalebone for structure, it supposedly took 3 hours to dress the King in his corset - the tightness of which nearly caused him to faint during his coronation. 14 References to men wearing corsets are peppered throughout the cultural consciousness - in the comedic opera "Lord of the Manor" by soldier and playwright John Burgoyne, a key character is described on stage as having "his stays laced". Apparently it was essential for the smart dressing soldier to incorporate stays into this dressing routines, for the improvement to the figure and posture in addition to the back support. One of the earliest mentions of military men in corsets refers to the officers of King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden. The officers of the famous "Lion of the North" were described as "the tightest-laced exquisites of human suffering". 15 Men's corset. Early 20th C. Men's corset. Early 20th C.In 1800's men were ordering leather corsets identical to women's: "We are informed that by one of the leading corset makers in London, that is it by no mean unusual to receive the orders of gentlemen, not for the manufacture of the belts so commonly used in horse-exercise [girdles], but veritable corsets, strongly boned, steeled, and made to lace behind in the usual way..." 16The lines and cut of men's clothing demanded a trim waist, whether the wearer had one or not. As the fashion for a man to have a wasp-like, narrow waist became more and more accentuated, the demands placed on the gent's stays became increasingly extreme. Just like their female counterparts, men were resorting to tight-lacing to hold in the belly bulge - and just like their female counterparts, there was an outcry from the medical community about the inherent dangers in such body modification. A gentleman wrote to the Englishwoman's Magazine with a scathing rebuttal of a woman's opinion on the tight-lacing of corsets, explaining that he and his "10 or 12" male friends at boarding school had been converted to tight-lacing and could not give it up: "the sensation of being tightly laced in an elegant, well-made, tightly fitting pair of corsets was superb." 17 An advert for men's and women's corsets. Late 1800's. An advert for men's and women's corsets. Late 1800's.

Part of the campaign to make men give up their corsets included portraying the wearers of such undergarments as effeminate and pathetic. The same pressure to give up the corset was applied to women - but a side-effect of the effeminate PR campaign allowed for the mentality that corsets were still permissible for women. While men discarded the garment towards the end of the 1800's - it would take some time and extreme cultural upheaval (WWI) before women would follow suit. 13. Schwartz, Jeffrey H. "Putting A Face On The First President". Scientific American. February 2006. 84-91. 14. Hogg, Meg. “Inside George’s Breeches: The Health of George IV.” Brighton Museums, April 22 2016, www.brightonmuseums.org.uk/discover/2016/04/22/inside-georges-breeches-the-health-of-george-iv/. 15. Berry, Lord William. The Freaks of Fashion: with Illustrations of the Changes in Corsets and Crinolines, From Remote Periods to the Present Time. London, Ward, Lock and Tyler. 1868. 16. Berry, Lord William. The Freaks of Fashion: with Illustrations of the Changes in Corsets and Crinolines, From Remote Periods to the Present Time. London, Ward, Lock and Tyler. 1868. 17. "Walter", Anonymous. Letter. The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine, November 1867.

|

|