|

|

Post by Aurelia on Jan 8, 2021 16:56:18 GMT -5

I'm going to just toss this thread here like a Ketchum grenade and see what happens. Who is responsible for the loss at Gettysburg? Did the Union really win - or did the Confederacy just hand it to them?  |

|

|

|

Post by andrew on Jan 8, 2021 18:01:33 GMT -5

You'd have to ask that question once for each day.

Day 1: The results of Day 1 I would say were simply an accident. Nobody knew where anybody was or in what strength. Curiously, neither side seems have engaged in any meaningful recce at all. The lack of cavalry was certainly a detriment to the south, but one doesn't *need* cavalry to scout. Union cavalry was, of course, fully engaged in defence.

Day 2: Confederate plans were uninspired, to say the least, but for the most part productive - though at least some of that success can be laid at the door of Union generals.

Day 3: I've read Longstreet's history and I still don't know how much credence to give his claims that he consistently argued for an end run around the Union lines rather than a frontal attack, but either way, the plan for Day 3 mystifies me. Antietam, Fredericksburg, Second Manassas - Lee knew the quality of the men he was facing, if not their generals, and he certainly knew what such men could achieve from an entrenched position against a frontal assault.

There's just no way a repeat of Day 2's frontal attacks, over open ground instead of the close ground of Day 2, and against a previously unattacked part of the line, could seriously be expected to succeed. I'll never understand Lee's decision on Day 3.

My verdict: Meade succeeded in not losing while Lee failed to win.

|

|

|

|

Post by Aurelia on Jan 12, 2021 18:16:17 GMT -5

You'd have to ask that question once for each day. Day 1: The results of Day 1 I would say were simply an accident. Nobody knew where anybody was or in what strength. Curiously, neither side seems have engaged in any meaningful recce at all. The lack of cavalry was certainly a detriment to the south, but one doesn't *need* cavalry to scout. Union cavalry was, of course, fully engaged in defence. Day 2: Confederate plans were uninspired, to say the least, but for the most part productive - though at least some of that success can be laid at the door of Union generals. Day 3: I've read Longstreet's history and I still don't know how much credence to give his claims that he consistently argued for an end run around the Union lines rather than a frontal attack, but either way, the plan for Day 3 mystifies me. Antietam, Fredericksburg, Second Manassas - Lee knew the quality of the men he was facing, if not their generals, and he certainly knew what such men could achieve from an entrenched position against a frontal assault. There's just no way a repeat of Day 2's frontal attacks, over open ground instead of the close ground of Day 2, and against a previously unattacked part of the line, could seriously be expected to succeed. I'll never understand Lee's decision on Day 3. My verdict: Meade succeeded in not losing while Lee failed to win. Meade really only had 3 or 4 days in command before Heth fumbled back through town and was confronted by Buford's cavalry. Poor guy thought he was being arrested when they brought him the command (not request) to take charge... so he wrote to his wife, saying the messenger came at 3 AM or so and said something along the lines of "I've come to bring you trouble". What Meade did right was call a counsel of War as his commanders assembled... Lee did not. J.E.B. Stuart was mucking about - at best he was caught up in a bad turn of luck, unable to get around the Union Army as they moved and at worse, goofing around. Supposedly on Day 2, there was a moment where the Confederates broke the Union center with 1500 men... but that was a day when they were also concentrating on avoiding flanking movements. I suppose It gave them reason to believe they could do it again the following day. Day 3, Confederates did break through at the Angle... but they just didn't have enough men to hold it... they captured the artillery at Codori Farm... but they were pushed right back before they really had a chance to turn the guns on the Union line. I sometimes think that Stuart was key in the outcome of Gettysburg... supposedly Longstreet had suggested getting between the Union Army and Washington (which would have been more threatening, I think... or if they had moved towards Harrisburg). So maybe Lee was more key in the defeat (he always allowed himself to take the blame after the war). But if Heth had followed orders and not engaged, maybe the whole story would have been different. |

|

|

|

Post by andrew on Jan 12, 2021 18:52:30 GMT -5

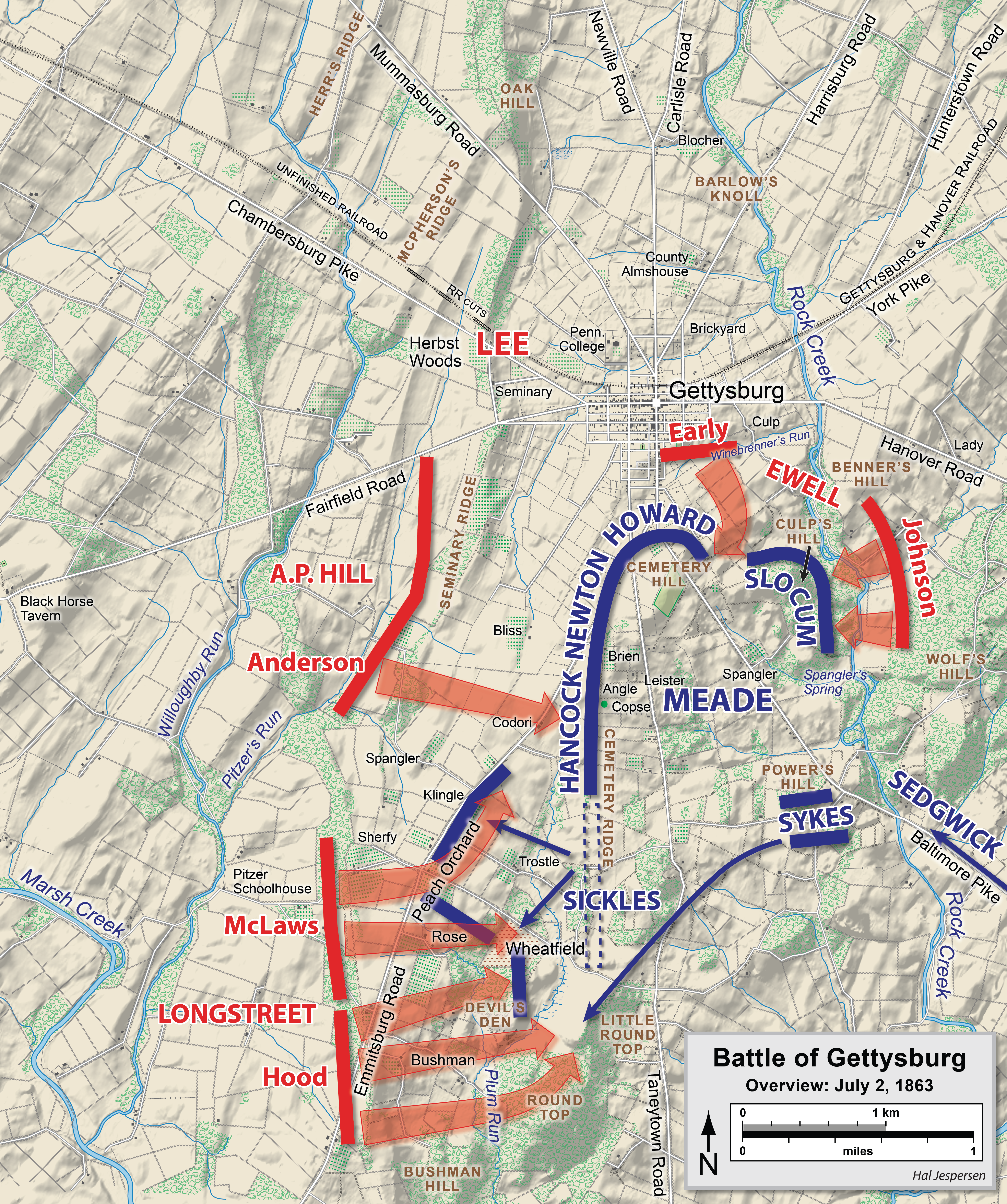

Now, my memory on this is a little hazy (I've officially forgotten more than I know - some years back, in fact), but the only real success of the south on day 2 was at the peach orchard, where Sickles had got ahead of the line and left himself exposed. The attacks on Culp's Hill and the Little Roundtop were repulsed with heavy loss. I'm not aware of any moment when the Union Centre was or could be said to be "broken". The missing Stuart on Day 1, mucking about or not, is kind of my point. In the absence of the intelligence he provided, southern commanders carried on anyway without conducting their own recce. Also Buford, once engaged, ceased any recce, and allowed Ewell to march his whole corps up the Union right flank with nearly disastrous results.   |

|

|

|

Post by Aurelia on Jan 14, 2021 20:05:19 GMT -5

Now, my memory on this is a little hazy (I've officially forgotten more than I know - some years back, in fact), but the only real success of the south on day 2 was at the peach orchard, where Sickles had got ahead of the line and left himself exposed. The attacks on Culp's Hill and the Little Roundtop were repulsed with heavy loss. I'm not aware of any moment when the Union Centre was or could be said to be "broken". The missing Stuart on Day 1, mucking about or not, is kind of my point. In the absence of the intelligence he provided, southern commanders carried on anyway without conducting their own recce. Also Buford, once engaged, ceased any recce, and allowed Ewell to march his whole corps up the Union right flank with nearly disastrous results.   They did push Sickles back on Day 2 - out of the Peach Orchard and Wheatfield and Devil's Den... all these men were crumbling back and slamming into men properly positioned behind them. The Confederates broke the Union line on Cemetery Ridge on Day 2 - it was nothing more than a break for a short time, but having done it with so few probably bolstered the decision for the following day. It would have been A. P. Hill making the break - Longstreet was busy shoving Sickles back.  Buford was rsther hopelessly outnumbered - he had the sense to see the ground and call for the infantry to back him up while he tried to hold it. It seems simple - it really is simple: he was doing his job (something Stuart was not 😜). He managed to hold till Reynolds appeared on the field, having his men fight dismounted with their supposed Spencer carbines (though there is debate on the exact weapon) - he got shoved some way back, but he was facing pretty unfortunate odds (2,700 versus 7,600). It was unfortunate that Reynolds had as an anticlimactic arrival - he seemed the one to take it all in hand and is promptly shot in the head. I always rag on Stuart... how hard was it to send someone with word to commanding officers? People tell me not to give him such a hard time, but it seems like the role of cavalry has altered so much by the Civil War that their main purposes were gathering information, relaying messages... seems like the real cavalry charges of the past were ever more rare. |

|

|

|

Post by andrew on Jan 15, 2021 21:49:58 GMT -5

Back about '95 or so I was killing time in Logan airport and picked up Pickett's Charge: A Microhistory of the Final Attack at Gettysburg, July 3, 1863 by George R. Stewart. It was the very first book I ever read about the American civil war and it blew my mind. I've read many more since then, but that one is still the best. If you haven't read it, I highly recommend it. It's been out since the 1950s so I'm surprised I hadn't seen it before then. "Microhistory" is not a joke; he breaks the "charge" down minute by minute. The one thing that really struck me was the professionalism of the southern troops. This was not just some rabble rushing out of the woods and doing a four-minute mile with fixed bayonets. It was a series of very precise oblique marches designed to reach a specific point. Now, anyone who has ever pounded a parade ground knows that there is nothing more difficult than an oblique march. That's marching at an angle, not straight ahead. To march a left oblique you stick your left leg out sort of sideways and up, then your right leg forward, then your left leg sideways and up and so on. They did this to limit the damage from Union artillery by keeping, so they hoped, their front to the enemy. They were all aimed at a specific point in the Union line and if they had all just marched straight for it, many units would have had to turn their flanks to the Yankee artillery. For an entire division (+) to do this, under fire, over such a distance, suggests a professionalism that would have made Napoleon proud. But I suppose the current social climate forbids acknowledging that southerners might have been competent. In the end it didn't matter. With batteries in the cemetery and on the round tops, they were enfiladed no matter which way they turned. And, if it isn't clear already, since reading that book I've never been comfortable with the word "charge" to describe this action. It was over a mile. A typical walking pace is about three miles an hour, so, even without halts - and there were several to reform - that's a minimum of twenty minutes. Twenty minutes in which, no matter which direction they were moving, they were enfiladed by artillery fire from at least one direction, sometimes more. They were downhill from the Union positions and any cannonball fired short would bound through them. (The Confederate bombardment, by comparison, firing uphill, wreaked its havoc not on the Union front line as they hoped, but on the supply trains and hospitals in the rear, as their shot bounced over the ridge). This map of the battle suggests that Kemper and Garnett made some kind of a left turn, but such is not the case. They marched to the left while keeping their front to the enemy.  |

|

|

|

Post by Aurelia on Jan 22, 2021 12:01:04 GMT -5

I didn't realize how difficult it was to march at oblique angles... though I do know that the goal was to keep their targeted point of attack somewhat ambiguous (which gets into the whole copse of trees debate). It must have been so much more difficult to do something so precise under that sort of fire - which as they approached the Emmitsburg Road would have been switched to anti-personnel artillery rounds. I think that it's easy to stand near the Virginia Monument on Confederate Ave and look out over the fields from the woods and think "What madman would have sent men into this sort of scenario?!" But hindsight is really 20/20... and when you think about the unknowns of the day and go to the Union position, it suddenly seems just as terrifying for the men on the ridge. The artillery bombardment was on the Union position was the largest concentrated artillery attack in history up to that point - it went on for 2 hours with something like 180 guns. From the Union side, on Cemetery Ridge, you would have been hugging the ground (or let's put it this way, I would have been!) if you were not working one of the Union guns. When the bombardment let up, you would start to stand up tall enough to peer over the hills that obscure the view and see... thousands of men moving steadily towards you. It must have been terrifying. There were Confederates who made it up to the Angle, and the 71st Pennsylvania called a retreat - in horror, the 59th NY fled just going with the momentum. This made two gaps in the Union line. Alexander Webb took several minutes to talk men of the 71st, 72nd (which coincidentally was a Zouave regiment... everything goes back to the Uniform thread... LOL!) and 106th Pennsylvania into a counterattack. In this time you had Confederates turning the guns they had captured around (though they had no ammunition) - and I suppose there was around this time the double cannister rounds fired into those few Southern men who were up on the Angle... that ended much of the forward movement. Still, you have to imagine the terror of being on the Union line for Pickett's Charge. There is a certain area in front of the Codori Farm where the ridges literally hide it from view. So you'd see these men walking from the woods, across the fields, and suddenly they were out of eye shot for long minutes - only to reappear directly in front of you as the mounted the crest of the little hill. I took some photos that show this last time I was at Gettysburg; though there are some other positions along the ridge with worse view of the ground ahead of them, these capture it a bit. Most of the field where the Confederates would have been marching would have been obscured until they mounted the little hill where the barn is located:    The guns at the Angle had a pretty clear view, however.    |

|

|

|

Post by andrew on Jan 22, 2021 15:46:21 GMT -5

Your images didn't load for me, but I hear you.

I thought I mentioned it in this thread, but I don't see it, so I'll repeat it. Your comment about laying down is spot on. The Confederate preliminary bombardment was almost completely ineffective, however terrifying, as the vast majority of their shot bounded over the hill and found targets among the supply trains and hospitals in the rear. Several Union caissons were exploded, but the damage to the front line was practically nil. That's one of the things Stewart examines in detail in the aforementioned book.

|

|

|

|

Post by Aurelia on Jan 23, 2021 12:48:58 GMT -5

Your images didn't load for me, but I hear you. I thought I mentioned it in this thread, but I don't see it, so I'll repeat it. Your comment about laying down is spot on. The Confederate preliminary bombardment was almost completely ineffective, however terrifying, as the vast majority of their shot bounded over the hill and found targets among the supply trains and hospitals in the rear. Several Union caissons were exploded, but the damage to the front line was practically nil. That's one of the things Stewart examines in detail in the aforementioned book. I hate it when my photos don't work! Google tends to change my share-ability to private whenever I add new images to public albums. I used to think the Confederates were just idiotic for missing targets - and that the Union gunners were very clever in that they silenced their guns one by one (in such a way that it resembled either being taken out or withdrawal), but supposedly this was par for the course. I got the chance to ask this question (basically "were the Confederate gunners incompetent?") to the host of a podcast dedicated to the battle of Gettysburg and was basically told that overshooting targets was common - the Union did it as well. I read up on it some and it seems like the rifled cannons (3" Ordinance and the Parrotts) had a range that could not be easily seen by gunners - they needed an observer or a balloon to help pin point their targets and check their accuracy. Then there was an issue with all the smoke that would have covered the battlefield; it would have been important to have someone able to observe the damage... supposedly the first few shots were very damaging, but after that the Confederates were more consistently overshooting. Once the Federal troops claimed the Round Tops, their signal corp was up there and was communicating to a small network of signal stations - this certainly ruined things for Longstreet on the 2nd by slowing him down as he had to find cover to move behind, but I could see where it would have been helpful for communicating during the 3rd as well. I've also read that just in general, the longer the range, the less accurate most of the guns became. The usual range during the Civil War was something like 800 yards - up to 1,200 yards (for greatest accuracy) - but some of the distances the Confederate guns were aiming for were over 1,700-6,000 yards away, so the accuracy of placing those shots became more and more unpredictable, even though the Parrotts would have helped them out a bit with sheer range. The last element that I've heard was possibly in play was that the Confederates were working with "defective" fuses. There were new suppliers providing the fuses for Confederates ammunition - testing done shortly after the battle revealed that the burn time of the fuses from the S.C. and A.L. manufacture was substantially slower than the fuses that had been used prior. The gunners needed to cut fuses something like an inch shorter to detonate at the same distance that the previous fuses had. If this was the case, it would have played a pretty crucial part in how shells exploded. I've also heard that the captured Union ammunition was not really compatible with Confederate fuses - the Confederates were getting much of their artillery from European sources versus the Union making their own. But again, you can find messages that reveal that "bad fuses" may have just been an excuse for user error / poor training. The "clever" act of silencing the guns one by one I was told was just a natural occurrence, as a messenger was sent from crew to crew with the orders to stop and conserve ammunition. It just so happened to appear as though they were withdrawing. I really wanted a moment of artillery genius to be credited for this, but meh... such is life. Sad. Sometimes I wonder what would have happened if the timing for Pickett's Charge had been different... had it been at dawn versus the afternoon... would it have taken more people by surprise? It seems odd that Pickett was given charge of it all (maybe a bit ominous), as he was not really one of the more trusted officers Lee had at his disposal. Lee was always taking the initiative - I guess if he had done otherwise it would be like a fox waiting in his den to be flushed out - so he was always on the offensive. Longstreet often cited the idea to draw the enemy out by getting between them and D.C. - but even moving towards Harrisburg would have been more effective, I think. (Harrisburg is kinda lame today... it this all occurred next week, I think the majority of people would say "sure, take Harrisburg - lol", but in the 1800's it was more of a happenin' place.) |

|

|

|

Post by andrew on Jan 23, 2021 14:39:47 GMT -5

There's also the real difficulty of shooting uphill at a target on the crest. If you shoot short, your shot either buries itself or bounces right over, depending on the angle of impact. Only a direct hit does any damage to the intended target. When shooting downhill, you can deliberately bounce your shot through the enemy ranks and too bad for them. As I recall, the great majority of Union soldiery assumed the prone position during the bombardment and would have been nearly impossible to hit with anything but air burst howitzers or unusual luck.

|

|