|

|

Post by Woland on Feb 10, 2021 23:14:33 GMT -5

1958

If 1958 was not the peak of Japanese cinematic art it was the peak of box office admissions: 1.1 billion was a mild increase on the previous year, the impact of TV on cinemagoers would not be felt for a couple more years. It also saw the release of Japan’s first full-length anime in colour: “Tale of the White Serpent”. An ideal blend of youth and experience combined with increasing use of colour and widescreen meant Japanese cinema was in a good place heading into the 60s. Tokyo in 1958, the famous Tokyo Tower in the background would be completed before the end of the year.

Building on the enormous box-office success of “Emperor Meiji” the previous year, Kunio Watanabe was hired to direct the yet another screen adaptation of “Chushingura”, the 1748 kabuki play based on the famous 47 Ronin who waited over a year to enact sweet revenge. With dozens of film versions over the decades it’s very hard to generate suspense in a story so familiar to Japanese audiences, being the second colour version of the story the movie opts to flaunt the impressive costumes with most of the action taking place indoors, an all-star cast including Kazuo Hasegawa, Machiko Kyo and Shintaro Katsu (who would play the blind swordsman Zatoichi in the 70s) adds to the interest but for the most part this feels quite a safe and restrictive film version.

The 47 Ronin

Turning out good family dramas with metronomic regularity was Mikio Naruse’s forte in the 1950s. He adapted the award winning novel Anzukko (“Little Peach”), a semi-autobiographical work by poet and novelist Muro Saisei, the finished film has a mild resemblance to “Sound of the Mountain” released four years earlier. Heishiro Hirayama (So Yamamura) is a famous writer living in the country with his wife and two grown up children. His daughter Kyoko (Kyoko Kagawa) keeps turning down potential husbands until a close friend Ryokichi (Isao Kimura) makes an offer. He’s a book lender, qualified in electronics and an aspiring writer, they move to the highly competitive Tokyo and struggle to make a living. He retreats into his proud shell, finding solace in alcohol and growing resentment of his successful father-in-law, she’s forced to borrow, sell belongings and hustle to keep a roof over their heads. As the marriage deteriorates she finds herself returning to her father for advice, his aphorisms on love and marriage provide sparks of light in an increasingly dark film as Ryokichi becomes more erratic and less respectful. The viewer wonders why Kyoko doesn’t just divorce him, but as her father says “Marriage is a battle”. Serving as counterpoint to the main story, Kyoko’s brother Heinosuke marries a young woman accustomed to a lavish lifestyle, a more realistic model for Ryokichi if he can’t live up to Heishiro as a man or writer. A fine film by Naruse’s standards even if Ryokichi’s antics become rather tiresome by the end.  Kyoko Kagawa and So Yamamura on one of their walks in "Anzukko"

“Summer Clouds” directed by Naruse shows just how far modernisation affects the Japanese countryside. A war widow named Yae (Chikage Awashima) runs her own farm despite her intrusive mother-in-law, at the start of the film she’s being interviewed by a reporter over a land reform program that will shape the lives of farmers like herself. Most of the film revolves around her brother Wasuke (Ganjiro Nakamura) and his large extended family: two ex-wives and a current wife plus several children from each marriage. Wasuke’s plans for his three sons differ from their own individual plans: one is an office worker wanting to move to Tokyo, another wants to be a mechanic, but Wasuke wants his youngest to marry a girl from a neighbouring farm to unite the fields, he’s also worried about his peasant son marrying an educated woman. Notions of modernity are in the air, as Yae begins an affair with the married reporter, she also takes driving lessons and writes her own stories in the local newspaper, while one of her old schoolfriends is now a successful restaurant owner in the city. Confronting the urban rural divide along with the work/life balance and a changing society, the movie feels emotionally flat with lots of expository dialogue, it has the elements of a great story but can’t quite fit them all together.  Yae and the reporter admiring the beach.

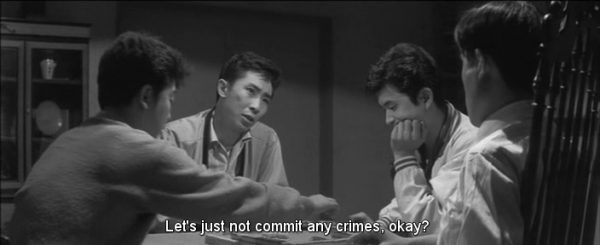

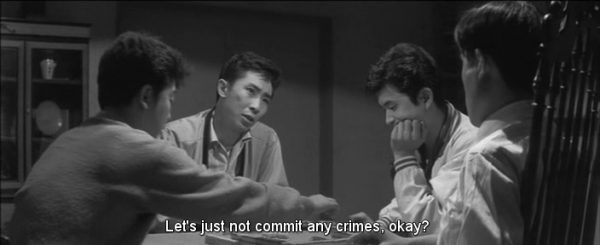

Toshio Masuda is better known for directing the Japanese section of “Tora Tora Tora” along with several other action movies, early in his career he churned out 6 movies for Nikkatsu in 1958 alone. Out of those films “Rusty Knife” made the most money at the box office for its noirish tropes and glimpse at the growth of organised crime. Starring 50s singer/actor and youth icon Yujiro Ishihara, it starts off semi-interesting with a small cameo by a young Joe Shishido until it becomes a very silly crime flick in the second half. To think “Perfect Game” was made by the same director in the same year is scarcely believable. The camera circles around four students too busy playing mahjong to care about their studies. All of them come from wealthy backgrounds, Soji (Akira Kobayashi) having the best social connections. With the job market so tough de facto leader of the gang Toda (Yasukiyo Umeno) comes up with a betting scam, they’ll make enough money to pay off all their short-term debts and they won’t have to work anytime soon. The scam relies on exploiting a 5 minute gap between a cycling race and the phonecall reporting the results. We see the gang practise the scam, the codewords and signals used to pull it off, they’ll have to bring in a couple other people but the payoff will be worth it.  The four students playing mahjong After the scam succeeds the gang are faced with one problem, the bookie with yakuza ties doesn’t have enough cash to pay their winnings, diving further into immorality they kidnap his sister until he pays up. From here on out the gang discovers just how dangerous and willing (or unwilling) they are for the cash, things spiral out of control as the bookie’s sister Kyoko becomes a pawn in their little game, things spiral out of control with deadly consequences. Based on a story by Shintaro Ishihara (“Crazed Fruit”), it’s a fine crime film playing to the Sun-Tribe subculture crowd with a jazzy score, out of the early crime flicks released by Nikkatsu in the late 50s this one is one of the better ones. Also making his first film in colour, Yasujiro Ozu returns to his familiar generational divide and marriage plots. Executive director Waturu Hirayama (Shin Saburi) is considered the go-to guy by all his friends and co-workers for advice on marriage and relationships, he’s already got a match for his eldest daughter Setsuko (Ineko Arima). A spanner in the shape of Taniguchi (Keiji Sada) enters his office one day and asks for his daughter’s hand in marriage, explaining they’re co-workers in a chemical plant and he’s being transferred to Hiroshima very soon. Waturu is disappointed at being left out of his daughter’s life decisions, he feels a loss of respect and power, even moreso when Setsuko declares she’ll marry Taniguchi anyway. When asked by a friend for marriage advice there’s a great contradiction in Wataru’s worldview: open-minded over a stranger marrying for love but not his own daughter. Another strong addition to Ozu’s oeuvre even if he’s handled this theme better in the past. This scene early in the movie shows Wataru giving a speech at a friend’s wedding, admitting his own marriage to Kiyoko (Kinuyo Tanaka) was arranged and not based on infatuation. Goichi Mizoguchi is the son of a priest being questioned by police over burning down a temple, motive unclear, he’s stubbornly silent. Through flashbacks we piece together bits of his life, his mother’s infidelity and her wish to see him become Head Priest, his father’s death from tuberculosis, his stammering fills him with shame, he loves the beauty and purity of the temple, it doesn’t belong to anyone, it has always existed and always been beautiful. Artfully photographed by Kazuo Miyagawa and loosely based on the novel “Temple of the Golden Pavilion” by Yukio Mishima, “Conflagration” feels like a series of barely connected scenes from the novel, ideas are hinted at without being explored. Later in life Kon Ichikawa insisted this was the favourite of all his own films. For his performance as Goichi Raizo Ichikawa won best actor at Venice film festival in what turned out to be a short-lived career, Tatsuya Nakadai and Ganjiro Nakamura offer strong support in a movie which may need familiarity with the novel to get the most out of it. A colour remake of a 1943 film by the same director, Toshiro Mifune plays the rambunctious “Rickshaw Man” with a heart of gold. Set in the early 20th century and filmed with an earthy palette of browns, greys and yellows the film begins as a comedy before switching to unconvincing melodrama, the first 30 minutes an excuse for Mifune to get into lovable hijinks: getting bashed in the head by a kendo master and cooking up a stink at a theatre among his escapades. A little later he befriends the recently widowed Yoshiko (Hideko Takamine) and her little boy Toshio, becoming a surrogate father for the latter and a close friend of the former. As the years go by “Wild Matsu” is still beloved by everyone in the neighbourhood for his big heart, full-blooded approach to life despite his poverty, Mifune channels his inner Kikuchiyo for sympathy. Despite star cameos from Seiji Miyaguchi and Chishu Ryu the film relies too heavily on Mifune, the screenplay moves in fits and starts unsure if it wants to remain a comedy or be a tearjerking melodrama, the death of Yoshiko’s husband happens far too quickly, the first 30 minutes are quite superfluous while the wheel-spinning montages near the end become very repetitive.. An almost forgotten winner of the Golden Lion at Venice, some flashbacks add little to the narrative heft, the timeline moves forwards several years at a time yet Yoshiko barely ages. A crowd-pleaser for Toshiro Mifune fans only. Coming off the darkness of “Throne of Blood”, Akira Kurosawa wanted to make a light-hearted comedy about two bickering peasants (Minoru Chiaki and Kamatari Fujiwara) lured by gold into escorting a Princess and a General (Toshiro Mifune) across enemy lines. “Hidden Fortress” is atypical of Kurosawa’s oeuvre, whether it’s a sign of versatility or proof he should stick to samurai movies is based on how much you enjoy the comic relief of the two peasants arguing which can be overstretched at certain points. It was the first Kurosawa movie filmed in widescreen, it was also Kurosawa’s most successful film at the box office in Japan, ironically it didn’t perform as well in America. Today the movie is better known as the inspiration for “Star Wars”: George Lucas turned the two peasants into C3PO and R2D2, the original screenplay for “Star Wars” was modelled on “Hidden Fortress” too. An executive asks whether Japanese kids will go for space toys like American kids, another fires back “you’re outdated, Japan is America”. A satire on ruthless corporatism and superficial consumer culture, in “Giants and Toys” the tranquil-eyed Nishi works for “World”, a caramel company in the cut-throat world of advertising against their rivals “Apollo” and “Giant”. He has to discover his rivals plans even if that means going up against old friends and a potential new flame. His superior Goda is young and hungry for success by any means necessary, turning a gap-toothed girl off the streets into an overnight celebrity. Filmed in pop art primary colours, office conversations are curt and direct: every second costs valuable yen. Not the subtlest film in the world, it was released around the same time television was replacing radio as the most popular mass medium; in today’s social media age its message has remained relevant. This scene depicts a corporate meeting at “World” discussing how to exploit their rivals misfortune. Two men board a crowded train on a stifling hot day, no available seats means sitting in the aisle for most of the trip. They end up in Saga Prefecture in Kyushu (over 500 miles from Tokyo), we find out they’re detectives taking a second storey room overlooking a small house. Thus begins “Stakeout”, a near two hour film based on a short story which doesn’t drag or feel too padded out. Through flashbacks we learn the older detective Shimooka (Seiji Miyaguchi) is married with an understanding wife and a not-so-understanding son, the younger detective Yuki (Minoru Oki) has a potential wife lined up but he’s afraid of commitment and his lack of salary. They’re interested in the ex-girlfriend (Hideko Takamine) of a wanted killer, Yuki has a hunch he’ll see her but there’s no guarantee of results. Shimooka and Yuki following the criminals ex-girlfriend, the first glimpse of rain in the movie At first the detectives have to stave off boredom and the oppressive heat, the ex-girlfriend is married to an older man with 3 kids from his previous marriage, she follows the rigid routine of a housewife without any excitement, “how can this woman be romantically linked to a killer?” Yuki thinks to himself. As the story unfolds characters become more complex, initial judgements are proven wrong, even the proprietress of the inn suspects the two men are up to no good. Filmed in gorgeous widescreen, aerial and tracking shots are used to good effect in the second half of the film, replacing the cramped sweatiness of the first half. Overall a polished police procedural and social commentary Taken from the debut novel of controversial writer Shichiro Fukazawa, the 1958 version of “The Ballad of Narayama” is a tale of a poor mountain village and its customs. Featuring more songs and less bestiality than the Palme d’Or winning 1983 screen adaptation, Keisuke Kinoshita’s version still delights viewers with its deceptively extravagant sets, exciting transitions between scenes and highly stylised colour cinematography in widescreen format. We see the village go through its festivals, accusations are made and transgressions harshly punished. The artificial sets and intense colours heighten the dramatic impact of the story, concerning the custom of 70 year olds being carried up the mountain and left to die for the good of the village. Gorgeous visuals on display

The elderly Orin (Kinuyo Tanaka) is approaching 70 and needs to settle her affairs before she dies, namely finding a wife for her widowed son Tatsuhei (Teiji Takahashi), who is reluctant to carry out the deed while her grandchildren are happy to see her go, more food for them. Her acceptance of death lies in stark contrast to her neighbour Mata-yan (Seiji Miyaguchi). It was rated film of the year by Japanese critics and holds the distinction of being the final film added to Roger Ebert’s list of “Great Movies” before his death in 2013. A lush, exciting blend of cinema and theatre, it received mixed reviews when screened at Venice yet was good enough to be nominated for the Golden Lion. Keisuke Kinoshita may not have the international reputation of Ozu or Kurosawa but his domestic reputation remains very strong, "Ballad of Narayama" being proof of that. Shohei Imamura served as assistant director under Yasujiro Ozu and Yuzo Kawashima. Determined to make films the complete opposite of the former he began his career studying the life of the lower classes in a comedic manner. “Endless Desire” focuses on 5 people meeting up at a train station, 10 years earlier on the last day of the war Lieutenant Hashimoto buried a cache of morphine now worth millions, the late Hashimoto’s sister and 4 men plan to tunnel their way to the treasure but can they trust each other? They rent a small place near the treasure spot under the pretence of an estate agency, having to hire a local lad to further said pretence. As the plot unfolds and they tunnel closer to their goal the human element intervenes, forces outside their control upend their plans, someone isn’t who they claim to be, doubt and panic creeps in. A fun crime caper and minor social commentary on the tough post-war job market, Imamura would become an important director in the burgeoning "New Wave" movement. |

|

|

|

Post by Woland on Feb 15, 2021 2:01:37 GMT -5

1959

Depending on who you ask, 1959 is either the end of the Golden Era or the beginning of the end. Certain trends such as increased violence and less reliance on major studios was becoming a factor, that didn’t stop a slew of excellent films to round off the decade. Tokyo, 1959

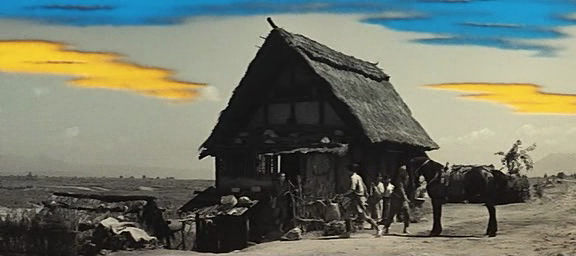

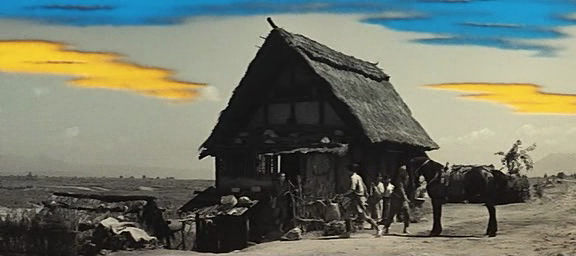

After the war American G.Is returned home, some with Japanese wives and some left mixed-race children behind in Japan. “Kiku and Isamu” live with their grandmother in a rural village, their mother died and their black father lives in America. Their neighbours have accepted them as Japanese without problem, strangers are surprised to see dark faces eating rice cakes and speaking Japanese, some of the kids at school tease them for being different, other adults worry about their future. Their grandmother told 11 year old Kiku their tanned skin would disappear with age but she isn’t buying it. The young boy Isamu doesn’t consider himself different, he’s surprised when another kid at school calls him “blackie” out of anger. The grandmother is pushing 70, so hard up for cash she can’t afford injections for her bad back and wants her grandchildren’s futures secure after she’s gone. Her doctor tells her there’s an organisation willing to take mixed-race children to America, later Isamu is asked if he wants to leave for the Land of Opportunity but the neighbours are unsure: discrimination still exists in America, Isamu would be wrenched away from familiar faces without receiving the same affection. Kiku on the other hand excels at sports but she can’t devote all her time to school, she has to help her grandmother on the farm. It’s believed she’ll have a hard time finding a husband or being accepted in society, Kiku’s teacher tells her if she knuckles down at school she can make a career for herself, she doesn’t have to be a simple housewife. Being the first Japanese movie to show black asians and deal with interracial relationships, it’s a fascinating social document that doesn’t get too bogged down in sentimentality, Yoko Mizuki’s script is nuanced enough without being preachy while the performances from non-actors is surprisingly good, winning “Best film” awards from 3 separate publications. In the final stages of WW2 in Manchuria, a reporter called Araki (Makoto Sato) turns up at a frontier town/military headquarters Shogunbyo, one of the prostitutes at the brothel called Tomi recognises him, they were once engaged until he disappeared. He’s intent on travelling to the infamous “Desperado Outpost”, an undermanned and undersupplied outpost behind enemy lines, so dangerous all the soldiers there believe it’s only a matter of time before they’re all wiped out. Everyone he comes across calls him a madman for going there, he’s not phased by their predictions of certain death. Once there Araki wants to know more about a double suicide in the middle of a battle, turns out the man was his brother and it wasn’t a suicide. Borrowing tropes from Hollywood westerns, “Desperado Outpost” throws in a murder mystery, tale of corruption and some explosions for an unusual film experience, throwing in a little dark comedy along with critiques of the Japanese military. The director Kihachi Okamoto was inspired by John Ford’s “Stagecoach”, shaped by his WW2 experiences in the Air Force (he later called his survival as a miracle), he served as assistant director under Mikio Naruse and Ishiro Honda, becoming one of the lesser known action directors at Toho Studios. An entertaining flick with an amusing cameo by Toshiro Mifune as an insane Battalion commander.  Japan doubling as the Manchurian steppe

“Samurai Vendetta” was one of the more violent chambara movies of the 1950s, its two main characters being the fictional Tange Tanzen and the historic Horibe Yasubei (one of the 47 Ronin), two samurai expelled from their respective schools for differing reasons: Yasubei killed several men in one fight and his school can’t keep him on their roster, Tanzen’s refusal to intervene in the fight (he was on shogunate duties) is seen as cowardice. Not even the appearance of Chiharu, engaged to Tanzen and desired by Yasubei can spur the two to fight each other. Told in flashback from Yasubei’s point of view, the film explores the navigation of samurai codes and honour through two men, both (including Chiharu) are targeted by vengeful samurai using underhand tricks to gain vengeance: Tanzen and Yasubei are far too skilled with the sword to be taken one-on-one. Yasubei joins the Asano clan who would later gain vengeance on Lord Kira in the familiar story of the 47 Ronin. One of the screenwriters Daisuke Ito directed several (now lost) swordfighting films in the 20s and 30s, the sight of spilled blood and a lopped off arm a sign of the bloody direction samurai films would take in the following decade. Shochiku studios wanted to counter the growing new wave market by encouraging first time directors, the directorial debut of Nagisa Oshima clocks in at just over an hour. “A Town of Love and Hope” is an examination of class in Tokyo centred around Masao, a young boy mired in poverty resorting to selling pigeons to passers-by knowing the pigeons will return home to him. His mother is sick and his sister stays at home drawing pictures of dead animals, the mother wants him to get an education to rise out of poverty. One day an upper class girl named Kyoko buys one of his pigeons, Masao’s teacher hopes the connections can help Masao land a job to make some real cash, once Kyoko finds out about the long-running scam she no longer sympathises with Masao, seeing him back on the street selling pigeons she buys it one last time and insists it won’t be returning home. Nagisa Oshima became one of the most prolific, versatile and controversial Japanese directors of the 60s, often connected to the “new wave” label he disliked, his notoriety would increase in the 70s and 80s.  Do not accept pigeons from this boy

Two lovers are canoodling in a not-so-secluded forest, Kikuko (Yoko Katsuragi) is cheating on her professor husband (Seiji Miyaguchi) with one of his students Ikuo (Takao Ito). She tells him she wants to be with him forever but she knows this is a lie, she talks about his potential future, a degree, a career, a marriage. Their loving conversation is interrupted by car headlights, a struggle is heard, the two lovers quickly leave. The scene of their affair becomes the scene of a murder, Ikuo wrestles with his conscience over civil duty, to come clean would ruin the reputation and marriage of his lover and her wife. She on the other hand is neglected by her intellectual husband, drawn to Ikuo through loneliness yet her middle class lifestyle cannot be ruined. Bringing together the Ko Nakahira-Shintaro Ishihara formula that worked so well on “Crazed Fruit” three years earlier, “Mikkai” keeps the tension in the story ticking over, the wife’s loneliness leading her to cooking classes and a meeting with the promising young student. From the long-take opening scene to the shock ending, “Mikkai” is a decent if under-seen tension puller at a brisk 75 minutes.   The two lovers in the opening scene.

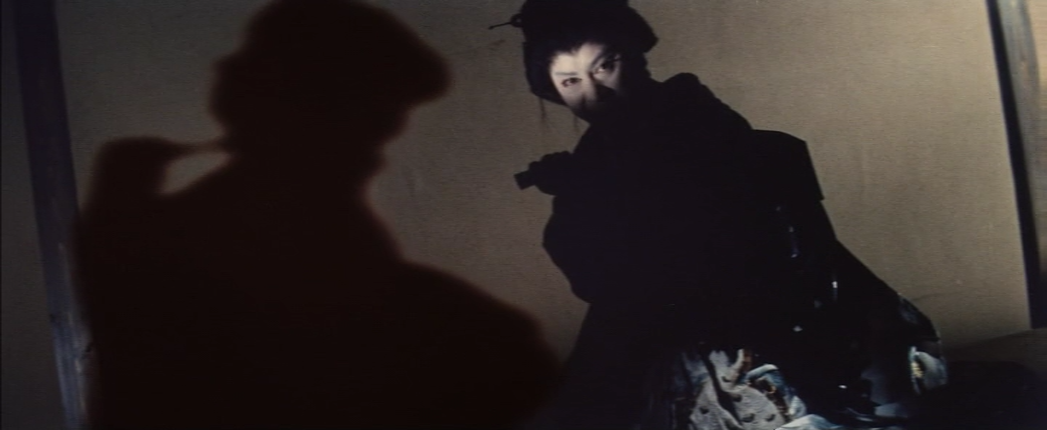

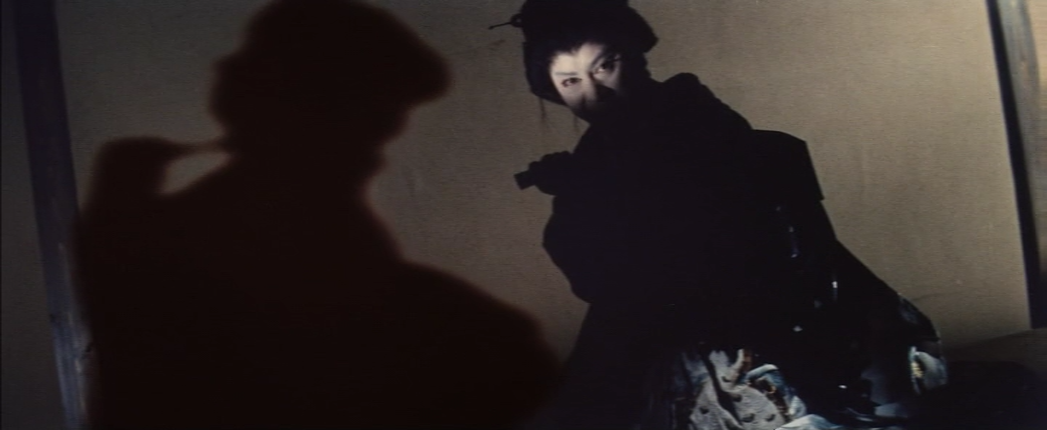

“Ghost of Yotsuya” is a famous ghost story adapted from a 19th century Kabuki play with several film adaptations over the decades. The 1959 screen version from Shintoho studios is one of the better known versions along with the 1949 version directed by Keisuke Kinoshita and the 1965 “Illusion of Blood” starring Tatsuya Nakadai. The story tells of a lowly scheming samurai Iemon Tamiya wanting to marry Oiwa, with a little help from Naosuke who wants to marry Oiwa’s sister he murders his way to her hand in marriage. A year later Iemon is married to Oiwa with a baby son, but he’s not content, chasing after Ume the daughter of a wealthy nobleman. This time Iemon poisons Oiwa and bribes the masseuse Takuetsu to seduce his wife so that Iemon can legally kill her for adultery. As the poison causes Oiwa’s face to break out into boils, Takuetsu confesses Iemon’s role in the poisoning, Oiwa swears revenge from beyond the grave as Iemon with multiple murders on his conscience sees her everywhere he goes. Hallucinatory visuals and snake symbolism abound in the second half of this relatively low-budget horror tale, another sign of the violence and disturbing imagery to come in the 60s. Not everyone handles their own decline with grace, certainly not the respected art connoisseur Kenji (Ganjuro Nakamura). Suffering from high blood pressure and needing injections to treat impotence he finds jealousy a wondrous aphrodisiac. His younger and obedient wife Ikuko (Machiko Kyo) can’t handle alcohol and passes out in the bath, his daughter Toshiko (Junko Kano) is engaged to the young and handsome doctor Kimura (Tatsuya Nakadai). Kenji tries orchestrating his wife and the doctor into having an affair to get his own mojo up, his daughter finds the whole business twisted. Based on the novel “The Key” by Junichiro Tanizaki, “Odd Obsession” is an unsettling movie, visually striking at times with precise framing to keep the nudity down. The twisted psychology of each family member keeps the viewer’s interest but the movie suffers from two main problems: no matter how much makeup you use Machiko Kyo looks too young to have a 20-something daughter, one plot device involving a colour-blind canister gives the abrupt and unconvincing ending away. It might need a couple viewings to understand its intricate character motivations.  From left to right: Kenji, Ikuko, Toshiko and Dr. Kimura

Showing enough versatility to piss off auteur theorists, Kon Ichikawa directed the harrowing “Fires on the Plain” in sharp contrast to the more sentimental “Burmese Harp” a few years earlier. Based on an award-winning novel, the story is set on the Philippines near the end of WW2, Private Tamura (Eiji Funakoshi) wanders through the desolate landscape, witness to the horrors of war all around him. To achieve authenticity actors ate very little and weren’t allowed to brush their teeth, things got so bad Eiji Funakoshi collapsed onset, production was shut down for 2 months. Full of bleak images with a hint of black comedy, some audiences and critics found it too dark and depressing to stomach. Over time its reputation has grown in stature, now considered one of the bleakest “war is hell” films out there. This scene points to one of the more controversial aspects of the film: cannibalism. In 1959 Yasujiro Ozu decided to remake a couple of his own silent films into colour. His best silent film “I was born, but…” turned into “Good Morning” with a modern twist: instead of two boys angry at their father’s brown-nosing at work they refuse to talk until their father buys them a television (one of the latest gadgets for each household along with a washing machine). Most of the action takes place in a close-knit neighbourhood, the two boys follow the sumo wrestling on TV at a neighbour’s house and want one for their own home, their conservative father (Chishu Ryu) doesn’t want his sons to become one of the “100 million idiots created by television”, so they go on a silence strike. A separate plot strand focuses on the local women’s club and payment or non-payment of dues between the mother of the boys Mrs Hayashi (Kuniko Miyake) and the chairwoman Mrs Haraguchi (Haruko Sugimura). Everyone living in such close proximity means rumours are easy to start and hard to stop, causing several misunderstandings. Sometimes known as the “Ozu fart film”, flatulence becomes a running gag throughout the film: the boys and their school friends all try to fart when tapped on the forehead, one neighbour’s farts are mistaken as a call to his wife, one boy’s unsuccessful attempts at farting means his mother has to wash his underwear all the time. Farting wasn’t completely off limits in Japanese art: one scroll from the Edo period depicts “fart competitions” and the novelist Natsume Soseki also discusses farting in one of his novels. The film’s major theme is communication, in the middle of the novels the father gets angry at the boys for talking too much, the eldest son replies about the superficial small talk adults engage in all the time. A more direct remake of his 1934 silent film, “Floating Weeds” is set in an idyllic coastal town, a troupe of travelling actors arrives to put on a new show. The ageing master of the troupe Komajuro (Ganjiro Nakamura) has a past history with the place: his old flame Oyoshi (Haruko Sugimura) lives with their son Kiyoshi (Hiroshi Kawaguchi) who believes Komajuro is his uncle. Komajuro wants to make up for lost time with a small fishing trip, but his current mistress and lead actress in the troupe Sumiko (Machiko Kyo) bribes a younger actress Kayo (Ayako Wakao) to seduce Kiyoshi. On paper the storyline sounds melodramatic, in the hands of a master director like Yasujiro Ozu the finished product is one of the director’s finest films, an excellent blend of comedy, pathos and drama. Made under Daiei studios the film’s glorious use of colour is testament to Kazuo Miyagawa, best highlighted in this wonderful scene between Komajuro and Sumiko. Without his famed red teapot, an umbrella adds a vivid flash of red to the dark shelters separated by an alley in the rain, some of the lines in the movie have a kernel of reality to them: Ganjiro Nakamura was a famous Kabuki actor before entering films in his 50s, while Machiko Kyo was a dancer at Daiei studios before becoming romantically entangled with its President who groomed her to international stardom. In 1958 a six-volume novel by Junpei Gomikawa sold 2.4 million copies in its first three years of publication. The movie rights were snapped up by Shochiku studios as a highly anticipated epic film trilogy went into the works. Made over 4 years and costing ¥ 270 million, “The Human Condition” trilogy is an enormous achievement in Japanese cinema, a critical and commercial success once described by British film critic David Shipman as “unequivocally the greatest film ever made”. Made up of six parts over three films, it clocks in at 9 hours 40 minutes. Chinese prisoners in a labour camp

Set in Manchuria during WW2, the film had to be shot in Hokkaido and all Chinese characters were played by Japanese actors: No way in hell would anyone Chinese have anything to do with a Japanese war film, diplomatic relations were non-existent between the countries and Japan wouldn’t formally apologise to China for its atrocities until the 70s (it had apologised to Burma, Australia and South Korea by then). The director Masaki Kobayashi felt a keen affinity for the novel and its protagonist: a socialist and pacifist, he was sent to Manchuria during the war and spent a year at a POW camp in Okinawa. While produced by Shochiku studios, the crew came from an independent studio Ninjin Club, including the cinematographer Yoshio Miyajima, whose use of tripods allowed for such precise camera movement Kobayashi said his shots looked even better onscreen than what took place onset. For the protagonist Kaji there was lots of speculation over who would play him, Tatsuya Nakadai had worked with top directors like Mikio Naruse and Masaki Kobayashi in supporting roles, “Human Condition” would be his first major lead role, an idealist in contrast to his earlier crazy roles. In “No Greater Love” Kaji moves to Japanese-occupied Manchuria with his wife Michiko (Michiyo Aratama) taking a job at a labour camp. Appalled by the treatment of Chinese prisoners, his idealistic proposals and morals aggravate his superiors and co-workers. Filming of “No Greater Love” was completed just two weeks before its premiere, all nighters were pulled to complete the editing and post-production work on time. In the second movie “Road to Eternity”, Kaji is drafted into the Imperial Army, undergoing a brutal training regime similar to “Full Metal Jacket”. During his time he befriends and loses several comrades due to the harsh conditions and borderline sadistic treatment from his superiors. Kaji’s idealism makes him despise the war even though he’s got it in him to be a great soldier, his sense of duty and compassion for his fellow suffering soldiers compels him to stick with the army. He’ll need to be brave because the Soviets are coming. During the six month interlude between films, some actors spent a month undergoing army training to prepare for the movie, in the days before health and safety regulations some scenes called for too much realism: in one beating scene Tatsuya Nakadai was really slapped and beaten until his face swelled up. In this battle scene he had to dive into a hole in the ground as a tank rolled over it. |

|

|

|

Post by Woland on Feb 19, 2021 4:16:58 GMT -5

1960

1960 was a year of political turmoil in Japan: a year-long coal miner’s strike in Kyushu saw strong labour unions go up against big business; the anpo treaty controversy spilled over from the previous year, seeing nationwide protests and rallies against the US-Japanese military treaty allowing use of American military bases on Japanese soil. On the cinematic front the year brought more movie theatres, produced more Japanese movies and higher box-office receipts than previous years. A diverse range of films by genre and style came out in 1960, some more politically charged than others.  Protests around Japanese Parliament building Yoshishige Yoshida’s debut film “Good for Nothing” showed how the economy affects three different men in Japanese society: a wealthy businessman preaching free markets and free competition yet willing to lend money to his layabout drifter of a son, another low-level salaryman is so obsessed with work and bills he can’t muster up enthusiasm over becoming a father. In his next film “Blood is Dry” he satirised the advertising industry and the superficial celebrity culture in a darker vein than “Giants and Toys” with a more socio-economic grounding. Keiji Sada plays Takashi Kiguchi, his small company is planning mass lay-offs to avoid going under, driving Kiguchi to a suicide attempt in front of his co-workers, practically begging to spare his colleagues’ jobs in exchange for his own life. An insurance company gets wind of the story and offers to make him the face of their new advertising campaign based around his suicide attempt, he reluctantly agrees thanks to a lack of money. A PR expert Yuki becomes his publicity agent organising interviews and public appearances to build up his persona and her bank balance, until he starts going to meetings and interviews not on her pre-approved list. Meanwhile a jealous paparazzo intent on making a name for himself tries to dig up dirt on Kiguchi, writing smear articles and organising set ups to besmirch his wholesome image. Kiguchi’s wife on the other hand is angry at his selfish suicide attempt, once he becomes famous she dislikes his new persona. While his initial appeal as an inarticulate everyman earns him fame and money in the short-term it comes at a long-term cost: his personality becomes dependent on the adoration of his fans, he begins to regurgitate the same slogans in everyday life claiming to want to help everyone, not realising the superficiality of his fame and recognition, or the impermanence of fickle celebrity culture. At the start of the film he needed a job to feel secure, at the end he needs the approval of faceless fans to feel secure. Two recent bank robberies leave the police completely dumbfounded, detective Okamoto (Tatsuya Mihashi) has a friendly rivalry with his reporter girlfriend Kyoko (Keiko Sata) trying to figure out who’s behind it. During a chase he stumbles across Fujichiyo (Kaoru Yachigusa), a former buyo dancer from a wealthy family ready to make a comeback. Is she linked to the bank robberies? Taking cues from Hollywood B-movie sci-fi, “The Human Vapor” ties “The Invisible Man” into a cautionary tale of science experiments gone wrong: turns out the “Gas Man” (Yoshio Tsuchiya) is a librarian who served as a fighter pilot until a cancer diagnosis forced him to quit. Upon recommendation he’s offered a chance to be a part of Japan’s Space Program to test the limits of the human body. Naturally the experiment goes wrong, the “Gas Man” becomes a murderer and bank robber to see Fujichiyo dance again. For all its cheesy special effects it’s a pretty decent B-movie in the end, building enough mystery at the start to unfurl the human story in the middle, setting up for the final showdown at the end. Ishiro Honda gets lambasted as a terrible film director, yet life-long friend Akira Kurosawa trusted him enough to be assistant director on the latter’s final 5 films. Nagisa Oshima did not look at the lower classes through rose-tinted lenses, in “The Sun’s Burial” he shows deeply flawed individuals mired in poverty, believing the Empire will return and can be built yet wallowing in nihilism, cynicism and morally objectionable scams. In his other nihilistic film “Cruel Story of Youth” he took to the streets of Tokyo with hand-held cameras, this time Makoto (Miyuki Kuwano) enjoys riding in cars with older men for fun until one tries to molest her, thankfully Hiyoshi (Yusuke Kawazu) is on hand to beat him up and save her. After they witness the Anpo protests he takes her to a nearby river and rapes her, the two begin a psychologically damaging relationship based on a rejection of society, Makoto moves in with him to escape her sister’s lectures. To finance their lifestyle they act out their first meeting: Makoto takes a ride with an older guy inducing him to molest her, Hiyoshi steps in to save her and blackmail him. When Makoto finds out she’s pregnant he tells her to get an abortion, he sleeps with an older lover and asks her for a loan to cover the costs. The shocking and disturbing subject matter earned the director plenty of controversy upon release, it was rejected for a UK cinema certificate. Now considered an important milestone in the “Japanese New Wave” for its daring content and challenging perceived norms, it’s too rough and raw around the edges, its criticisms too direct to be an easy watch. Taking a different look at relationships in a changing society, “Brother” is set in 1920s Japan based on a novel by Aya Koda. Hekiro (Hiroshi Kawaguchi) is a teenage boy prone to idleness, fighting, horse riding and gambling, his antics get him expelled from school. His sister Gen (Keiko Kishi) on the other hand has to do all the housework, the cooking and be the responsible one in the family: her stepmother (Kinuyo Tanaka) is bedridden with rheumatism while her father (Masayuki Mori) spends all his time writing alone. Gen’s mother complains about everything and doesn’t trust her, while Hekiro is spoiled and indulged by his father resigned to the fact “boys will be boys”, it’s certainly not a fair deal for Gen even when Hekiro tries to strangle her. As the story develops tragedy befalls Hekiro and it’s up to Gen to do her best helping him out. Centred around the high expectations of women in contrast to men and winning film of the year by Kinema Junpo magazine, “Brother” is most noted for its desaturated colour palette with high contrast thanks to an experimental colour process called “skip bleaching”, to achieve the period look for the film. “Night and Fog in Japan” deliberately takes the title of a Holocaust documentary released a couple years earlier. The film begins with a wedding between Reiko and Nozawa, what’s meant to be a joyous occasion turns sour the moment Ota turns up berating everyone for not being as dedicated to the student protest movement as himself, using multiple flashbacks from several other wedding guests to piece together the story of the failed protest against the US-Japanese treaty. Utilising long takes and stylised photography akin to theatre, it’s a stylistic detour from the other two Oshima films made that year, the overtly political dialogue will not be for all tastes, it works far better as a study of the internal dynamics of a failed political movement. After a Socialist party politician was assassinated by a right-wing student, the movie was pulled from theatres after 3 days, prompting an angry letter from Oshima denouncing Shochiku studios for the decision, he left and set up his own independent studio. The opening 20 minutes of “The Bad Sleep Well” is a textbook example of introducing a large number of characters and the interconnected relationships between them. A flock of reporters gather round a high-profile wedding reception, Iwabuchi (Masayuki Mori) is Vice President of Public Corporation, marrying his limping daughter Yoshiko (Kyoko Kagawa) off to secretary Nishi (Toshiro Mifune) to further the latter’s career. Iwabuchi’s son Tatsuo (Tatsuya Mihashi) is serving as master of ceremonies at the wedding reception until the Police walk in to arrest him for bribery and kickbacks. The reporters note a similar scandal several years ago involving Iwabuchi and his associates Moriyama (Takashi Shimura) and Shirai (Ko Nishimura), when Assistant Chief Furuya committed suicide to end an investigation into corruption. The wedding cake is wheeled into the room, an imitation of Public Corporation’s office building with an ‘X’ on the seventh floor, the same window Furuya threw himself out of. A noirish commentary on post-war Japan’s corporate cronyism, the film is loosely based on “Hamlet” as Nishi reveals his plans to destroy Public Corporation from within. At two and a half hours it loses a bit of steam in the middle and final thirds, some of the acting resorts to screams and squirms but as with Kurosawa some sequences including that opening are brilliant, this scene showing underling Wada witnessing his own funeral being one of them. “Black people invented jazz, white people stole it, and now we have it, we’re the worst”, says the psychopathic protagonist Akira (Tamio Kawaji) a former juvenile delinquent with a love of “real jazz”, laughing in people’s faces and eating like a pig. The moment he’s free he joyrides with a couple friends: Masaru (Eiji Go) lives with him in a tiny shack so close to the railway it rumbles everytime a train passes, Yuki (Yuko Chiyo) “entertains” foreigners for money and laughs so often she might be part-Hyena. Akira has a bone to pick with Fumiko (Noriko Matsumoto) the girlfriend of the reporter who got him locked up, he spends most of the film intruding in her life and getting her pregnant, she oddly feels something towards him despite her engagement to a reporter. The lack of plot gives an aimless feeling matching its protagonist, while his friend Masaru wants to join a gang to make some real money. At one point Akira drops in at Fumiko’s place with all her artistic friends around, one of them describes Akira as “the perfect image of Modern Man”. The use of handheld cameras and tracking shots as characters’ point of view, the frenetic jazz soundtrack and charismatic lead performance makes “The Warped Ones” an engaging, disturbing film, the opening gives you an idea of what to expect from the rest of the film. “River Fuefuki” is an ambitious film set in the 16th century (before Sekigahara and before Tokugawa Ieyasu becomes shogun), contrasting the fortunes of 5 generations of a peasant family with the fortunes of the Takeda clan, majority of the action occurring in a small home beside the titular river. The adult Sadahei (Takahiro Tamura) becomes the lynchpin of the story, for the first third we see his father, grandfather and uncle’s views on war, little Sadahei is born on the same day as the son of Lord Takeda. As the years pass Sadahei marries the lame Okei (Hideko Takamine) and after several attempts they have three sons and a daughter. Sadahei is worried about the “vigorous blood” flowing through his sons veins, he doesn’t want them dying in pointless wars. For experimentation purposes the movie uses tinting, filters and freeze frames to great effect, the use of coloured washes to imitate ancient scrolls is more distracting than anything else. Something of a mini-epic with historical battles dotted through the narrative, it’s more of a gentle flow than a grand sweeping narrative, cramming decades of storyline into two hours running time means characters are lightly developed and hard to empathise with. An interesting film that would’ve worked better as a mini-series.

The home next to the river with coloured washes.

Family and money don’t mix in this colour drama from Mikio Naruse. The story of an elderly widowed mother (Aiko Mimasu), the enormous house and the lives of her grown up children wanting that inheritance. The eldest daughter Sanae (Setsuko Hara) loses her husband in an accident early on in the film and moves back home until she can find a job or another husband; eldest son Yuichiro (Masayuki Mori) is a salaryman and head of the household looking for new investments even when his siblings are asking for money; his wife Kazuko (Hideko Takamine) is the subdued homemaker taking care of their young son; the second daughter Kaoru (Mitsuko Kusabue) can’t stand living with her henpecked husband Hidetaka (Hiroshi Koizumi) and his domineering mother (Haruko Sugimura; youngest daughter Haruko (Reiko Dan) injects some energy and fun into proceedings while youngest son Reiji (Akira Takarada) is a photographer who doesn’t get along with his wife. Sometimes reminiscent of lesser Ozu with a curious soundtrack mixing classical and melodrama, “Daughters, Wives and Mother” examines the generational gap between the older and younger siblings through Sanae: her traditional dress contrasts with her youngest sister Haruko’s modern dress and earrings, when she’s courted by the younger vineyard owner Kuroki (Tatsuya Nakadai) she talks about the age gap and how things were done in the past. The increasing modernity sees new gadgets such as washing powder, vacuum cleaners and home movies, but for Kazuko in particular the old gender roles still persist. Banking on its enormous star power and a cameo from Ozu regular Chishu Ryu, the movie was the biggest hit for Toho studios at the Box Office, for all its star power some of the plot points are clunky and the lack of an ending leaves a hint of dissatisfaction. Jiro Sano (Chiezo Kataoka) is a generous, kind-hearted textile factory owner living in the countryside who shows great compassion towards his workers, his dreams of an heir are scuppered by a disfiguring stain on his face, the reason his parents abandoned him as a boy and his marriage proposals are rebuffed. On a trip to Yoshiwara (red-light district in Edo) he becomes smitten with the only geisha not repulsed by his stain Tamatsuru (Yaeko Mizutani). Her story is equally sad: sold into prostitution and labelled by the other geishas as a common criminal unworthy of ever becoming a proper courtesan (tayu). The ruthless environment forces her to train harder and become a courtesan, Jiro wants to marry her and get that heir he craves. His benevolent manner towards his countryside workers is perceived as loose frivolousness by the inn-keeper sensing he can rinse Jiro out of enough money to turn Tamatsuru into a money-making courtesan; when Tamatsuru’s ex-husband tries to get money out of him he’s given harsh treatment and a striking night-time sword fighting scene. Jiro’s clients are worried by his spending habits in Yoshiwara, they don’t want him to have a playboy reputation, a damaging hailstorm and subsequent poor harvest soon turns his fortunes upside down as Tamatsuru’s star rises. The corrosive power of greed and desire for social acceptance are told in vibrant colours accentuating the appeal of Edo in contrast to the more muted textile factory in the countryside, the ending of “Hero of the Red Light District” is as shocking as Tomu Uchida’s earlier directorial effort “Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji”.  Jiro Sano and his facial stain.

“When a Woman Ascends the Stairs” explores the true cost of keeping up appearances in the upmarket Ginza district of Tokyo. Keiko (Hideko Takamine) is a bar hostess affectionately called “Mama” by all her friends and customers, business is falling thanks to a rival bar opened by her former employee Yuri (Keiko Awaji) hoovering up all her old clients, meeting up with Yuri later she learns her old employee’s success is built on mountains of debt. “Mama” switches to a new bar taking all her old staff and customers with her including her understanding manager Komatsu (Tatsuya Nakadai). She and Komatsu go back a long way: he hired her 5 years ago as a cashier and now she’s looking to open her own bar. He’s seen countless women succumb to the pressures of the lifestyle, eventually they all give in to a wealthy patron for that much needed cash, he admires Keiko for keeping her standards up: “if I let my standards drop I’ll give everything up” as Keiko says. Komatsu himself isn’t all that perfect, at the start he talks about “not fiddling with the goods” but he starts seeing his co-worker Junko (Reiko Dan) sheepishly noting “can’t avoid a little smudge with so many women around”. Keiko has three suitors vying to be her patron: an aged executive Mr Minobe (Ganjiro Nakamura), the unattractive factory owner Mr. Sekine (Daisuke Kato) and a married bank manager Mr. Fujisaki (Masayuki Mori), all three are willing to put money forward for her new place but she’s not willing to sell her body: she lost her husband in a car accident and swore never to give herself to another man. Such ideals are the only thing keeping her upright, deep down she hates having to walk upstairs to start her job, wearing expensive kimonos and perfumes to please clients, sending money to help out her family in need, eventually it takes a toll on her health. She looks for security in her loved ones but is frustrated and disappointed every step of the way, but the heroines in Mikio Naruse’s films do not give up so easily. The opening credits of “Hell” give you a taster of the horrors to come: a cloudy river doubling as Sanzu River, a man falling into a fiery circle, but before we find out what awaits him we return to the real world. Shiro is a promising university student, nice girlfriend Yukiko, the only problem in his life is the scoundrel Tamura. One night Shiro and Tamara run over a drunk yakuza, setting off a chain of events that’ll lead to murders, suicides, drunken parties and shootings. The final 40 minutes of the film are devoted to the brutal tortures of the afterlife: teeth are smashed, bodies sawn in half, impalement, you get the idea. Considered a cult classic in the horror genre, “Hell” was the last film made by Shintoho studios before it declared bankruptcy one year later, the histrionic acting and silly plot twists along with its name have given its detractors ample ammunition over the years. “Modern Film Association” was formed in 1950 as an independent film studio after directors Kaneto Shindo and Kozaburo Yoshimura left Shochiku, ten years later it was on the verge of bankruptcy, director Kaneto Shindo decided if the studio was going down he wanted to make one artistic film instead of something commercial. Intended as a “cinematic poem” without dialogue, “The Naked Island” was largely filmed on an uninhabited island, focusing on a small family with two young boys struggling for survival. The parents have to carry wooden buckets of water up a steep hill, the bend in the yoke and sweat-drenched faces a far better sign of the tough life than throwaway dialogue, the director’s intention was to "capture the life of human beings struggling like ants against the forces of nature.” A simple tale beautifully told, the strong visuals and haunting score a prime example of how unnecessary dialogue can be. The film won top prize at the Moscow Film Festival, its financial success saved the company which still exists to this day. |

|

|

|

Post by andrew on Feb 19, 2021 19:20:23 GMT -5

"Japan doubling as the Manchurian steppe" You reminded me of one of the funnier movie moments. I was watching some really bad samurai movie (Heaven & Earth - not to be confused with the Tommy Lee Jones movie of the same name) which, the more I watched, I began to think this can't be filmed in Japan. Then sure enough, there was a nice postcard shot of Banff, Alberta. And I would have been quite okay with that really if one of the characters hadn't gazed at it and exclaimed, "Ah, Mount Fuji!" I actually choked on my popcorn.   |

|

|

|

Post by Woland on Feb 28, 2021 12:40:51 GMT -5

1961

1961 is dubbed by the catastrophising-inclined as the beginning of the end of the Golden Era: a substantial dip in box office admissions a sign of rising television ownership and cinema ticket prices. The wide variety of film styles and techniques on display a sign of the young and old generations catering to different demographics, a couple younger directors looking for a new style far from their old masters.

Tokyo, 1961

The spectre of the nuclear bomb reappeared thanks to the controversial US security treaty in the middle of the Cold War. Toho studios produced two very different films on this topic: the big-budget “The Last War” was the studio’s second highest earner of the year and 9th highest overall. Viewing the escalation of WW III through the eyes of an everyman (Frankie Sakai) and his family, it’s reminiscent of films by Stanley Kramer, the preachy corniness saddled with an overbearing soundtrack is too distracting, the themes too on-the-nose, the english-speaking roles are filled by subpar actors with unconvincing dialogue, the Japanese roles include big name stars Chishu Ryu and So Yamamura as Prime Minister. When miniature models are the only good thing about a movie you know it’s bad. Anyone expecting swathes of wanton destruction will be disappointed by “Mothra”, a lighter kaiju film with hints of King Kong and shades of Disney. The story begins with four sailors washing up on a remote Pacific island that’s been subjected to nuclear testing, none of them have radiation sickness and one of them mentions natives on the supposedly uninhabitable island. When a joint Japanese-Rolisica expedition to the island discovers two 12-inch tall women (popular singing twins “The Peanuts”) the self-appointed head of the crew Clark Nelson (Japanese-American actor Jerry Ito) sees a business opportunity; when the natives try to stop him stealing the women a second time he guns them down. Disturbing the peaceful islanders brings grave consequences to Japan: Mothra is coming to rescue the two women no matter what. As a Japanese-American co-production bringing english-speaking roles into a Japanese film, part of the story had to be set in an American city, the fictional New Kirk City bearing the brunt of Mothra’s attacks, the fictional country of Rolisica (a mixture of Russia and America) allows its villainous citizen Nelson to get away with all sorts of crimes in Japan. To lighten the story comic actor Frankie Sakai gets plenty of screentime as a tenacious reporter with Kyoko Kagawa co-starring. The special effects and miniatures are a step above “Godzilla”, it’s a colourful trans-Pacific spectacle with an insanely catchy song, the pacing is just too slow to keep it interesting. The first film made by Nagisa Oshima after leaving Shochiku is “The Catch”, based on a novel by Kenzaburo Oe. A small mountain community in 1945 captures a black American airman, the villagers are split on what to do with him: some are in favour of killing him off, they can’t afford to give away vital food to him, others believe they should keep him prisoner until the authorities make a decision. He’s treated more like an object than a human being, called the ‘n’ word repeatedly, his bear trap is only removed after his wounds begin to rot, pretty soon he gets blamed for every misfortune befalling the village, the corrupt village chief tells them it’s the airman’s fault and he should be killed, the children protest but the adults obey. Another uncompromising look at the darkest aspects of Japanese society during the war (one kid sees Tokyo burning in the distance and celebrates), “The Catch” shows extremists aren’t born overnight and corruption can’t be weeded out in one day. The Sun-Tribe subculture raised alarm bells for the older generation worried about keeping the youngsters in line. A novel called “Wings that can’t fly” collected the experiences of juvenile delinquents in reform school, the novel became a cinema verite documentary on the reform system and the teenagers navigating it. It’s shot in black and white using non-professional actors, real life locations and improvised dialogue, the main character Asai has been arrested for stealing jewellery, through flashbacks and interviews we discover more about his past, we also see the inner workings of the system and whether it reforms people into good behaviour or reinforces bad. Winner of Best Film by Kinema Junpo magazine and an important social document of its time.  The juveniles being taught a lesson

In response to the increasing gore and violence of samurai flicks, Akira Kurosawa wanted to make a movie showing the damaging effects of violence, he later regretted “Yojimbo” for spawning a new genre of samurai flicks and spaghetti westerns; “A Fistful of Dollars” was an unofficial remake of the Kurosawa film, “Yojimbo” itself is loosely based on 1940s noir flick “The Glass Key”, taken from a Dashiell Hammett novel. The story of a wandering ronin (Toshiro Mifune) playing two sides against one another has become a bit of a cliché, the movie itself still holds up as good entertainment with a surprise turn from Tatsuya Nakadai as a psychotic gunslinger. “Yojimbo” and its sequel “Sanjuro” were massive earners for Toho Studios and Akira Kurosawa. Ayako is on trial charged with murdering her much older, academic husband Ryokichi on a mountain climbing trip: as the two of them dangled by a rope, Ayako cut the rope leaving her husband to fall to his death. The reporters believe it was murder, convinced by her friendship/romance with a younger man Osamu who was also present on the trip along with a lucrative life insurance policy taken out by Ryokichi. Serving as part courtroom drama and part commentary on freedom in a rigid society, we learn more about the loveless marriage through flashbacks, he’s only interested in drinking and mountain climbing, unwilling to grant her a divorce, she’s a war orphan who struggled to make it into pharmacy school. Osamu used to bring Ayako her medicine and felt sorry for her, the two developed a friendship which Ryokichi called “an affair”, despite Osamu’s engagement to another woman. During the trial the main sticking point is her reasons for cutting the rope: self-preservation or malice? A strong character study and taut thriller.  Ayako faced with the rope and knife in court

An absurd farce on sexism in society centres around a TV producer named Kaze, his wife and 9 mistresses, all of them wanting revenge for his philandering and none of them wanting the responsibility of knocking him off. Kaze doesn’t appear to be the suave casanova type with women falling at his feet at the click of his fingers, his job title is alluring enough for some women wishing to climb the greasy pole, Kaze himself is just a nice guy who doesn’t know how he’s managed to snag all these 9 mistresses, or the 30-40 others from work he’s had coffee with. All the women agree if he isn’t stopped he’ll surround himself with a new circle of mistresses, all of them still possess feelings for him but believe he must be killed for his own good. Filmed in noirish black-and-white, it’s a decent farce with some good moments but can’t quite live up to its great premise.  Kaze and his wife + 9 mistresses in the same room

Six years before Seijun Suzuki was fired over his incomprehensibly bizarre film “Branded to Kill”, another young director Masahiro Shinoda made a colourful send-up of the hitman genre. “Killers on Parade” has the standard story of a construction magnate wanting a journalist killed for fear of exposing widespread corruption, a guild of 8 assassins including a doctor (carrying a large bag with the word “doctor” in bold letters for the audience’s sake), a poetic youngster and a woman carrying her baby lamb around hold a contest to decide who gets to kill the journalist, until they’re pipped by an ordinary guy who’s a better shot than all of them. The film isn’t really about the plot, it’s the garish colours, random musical numbers and general absurdity of it all, thanks to the screenplay by avant-garde playwright Shuji Terayama. The movie was a big flop on release, Masahiro Shinoda had to direct more standard fare to get his career back on track, the opening credits give a hint of the impending silliness. Miho Nishigaki (Hideko Takamine) is pushing 40, lives with her grandmother and runs a Ginza bar. She’s spent all her life working her guts out and has nothing to show for it, the bar belongs to Keijiro (Masayuki Mori), a happily married professor with two kids and wife Ayako (Chikage Awashima). Miho tries a couple things to give her life some kind of meaning, she tries flirting with Minami (Tatsuya Nakadai) and she asks the owners for money to move into a new bar. It turns out Miho has been Keijiro’s mistress ever since the war, even more surprising she’s the real mother of his two children. A story needs a good foundation to help the audience suspend disbelief, “As a Wife, as a Woman” needs additional explaining to successfully change the “non-biological father” trope into a non-biological mother, once the secret is out in the final act it requires a lot of explaining from the main characters, the shaky foundations undercuts the strong acting and the icy scenes between Miho and Ayako. The story focuses on the plight of Miho but in the end the focus switches to the children who prove to be stronger than the adults.  The two children

Teiko gets caught in a whirlwind romance with a businessman called Kenichi ready to move back permanently to Tokyo, they’ve been married a week when he goes on a short business trip to Kanazawa to sort out some things, he doesn’t return. Teiko discovers some postcards hidden in a book and takes the long train journey to the west coast of snow-capped Japan to uncover the truth. Banking on the impossibility of knowing absolutely everything about someone, “Zero Focus” serves up enough plot twists to keep the audience hooked until its overly-talky denouement saps all the mystery and suspense away. Filmed on location in beautiful black and white, a solid mystery film with a beautiful score, Hitchcock fans may be disappointed. 1932 in a small village surrounded by picturesque mountains, Heibei (Tatsuya Nakadai) returns from the war in Manchuria crippled, somewhat comforted by his wealthy father’s estate and inheritor of all that land. At an event he falls for the attractive Sadako (Hideko Takamine) but she’s in love with the poor Takashi (Keiji Sada) currently serving in the war. Jealous of Takashi’s pristine image and bitter about his injuries he rapes Sadako while Heibei’s father uses his financial leverage on Sadako’s father to arrange Sadako’s marriage to Heibei, she tries to drown herself when she discovers she’s pregnant. Once Takashi returns from the war and finds out what happened he initially proposes to run away with Sadako but leaves without her, believing she’ll be better off in a rich household than being poor with him. Over the next four chapters spanning over 30 years we witness the loveless marriage from hell: Heibei is demanding and cruel, Sadako has to take care of her husband and father-in-law, she cannot bring herself to love her first-born son for what he represents. Takashi gets married too but he hasn’t gotten over Sadako; Heibei’s bastardliness doesn’t stop him molesting Takashi’s wife either. During the five chapters we see important changes in Japanese society, the land reforms of the late 50s strips away the samurai wealth of Heibei’s ancestors, his youngest son becomes a left-wing radical and the train makes its appearance too. Unlike the “River Fuefuki”, the shorter timeline combined with similar running time allows for deeper understanding of the characters, the passage of time feels stronger. It’s not easy seeing a married couple detest one another for decades, the weird choice of flamenco soundtrack and castanets is hit and miss too, the whole time one wonders if this was made in Hollywood it would be called “Oscar bait”, unsurprisingly the movie was nominated for Best Foreign Language Oscar.

Ageing Tatsuya Nakadai with his son

Shohei Imamura asserts himself as the Anti-Ozu in “Pigs and Battleships”, an exciting mixture of humour, cynicism and despair in the corrupt world of post-war Japan. Kinta (Hiroyuki Nagato) is a small-time hustler and wannabe yakuza, he profits off the nearby American naval base and gets a job taking care of pigs for the local gang. Examining the black market and the pimps, prostitutes and petty criminals making their living from it, its controversial depiction of a U.S military base and perceived anti-American views meant Shohei Imamura was barred from making films for the next two years. 1961 saw the final part of the Human Condition trilogy “A Soldier’s Prayer” released. Kaji (Tatsuya Nakadai) is stuck behind enemy lines, sick of war and fighting with a desire to return home to his wife, but things don’t go according to plan. Adapting a six-volume novel to a 10 hour film trilogy was always going to be a difficult task, especially with the time constraints and usual problems with making a movie. “The Human Condition” has been dubbed one of the greatest film trilogies of all time and one of the greatest anti-war films ever made, I don’t think any film can live up to those expectations but the attention to realism (where applicable!) is certainly impressive, a time when health and safety regulations means certain scenes can’t be filmed with the same sort of realism: in one scene Tatsuya Nakadai spent so much time in the cold he believed he was going to die from hypothermia. |

|

|

|

Post by Woland on Mar 10, 2021 13:41:29 GMT -5

1962

1962 saw the number of Japanese films fall below 400 for the year and audience numbers drop by 200,000. The smaller quantity of Japanese films appeared of higher quality than the past couple years. 1962 also saw a couple Japanese film icons bow out forever along with the birth of a new icon.  Hiroshima, 1962 To celebrate Toho’s 30th anniversary several big budget productions were announced including a new screen adaptation of the 47 Ronin. Clocking in at almost 3 and a half hours with an enormous ensemble cast, vivid cinematography and great sets it’s a very good historical epic, more expansive and cinematic than the constrictive 1958 version. An all-star cast including Toshiro Mifune, Takashi Shimura and Frankie Sakai makes it all the more impressive even if it requires familiarity with the story to follow it. Whereas the 1958 version was the highest-grossing film of the year, the 1962 version managed 8th place, behind “Miyamoto Musashi II” and “King Kong vs Godzilla”. The film was also the swansong of two icons of Japanese cinema: Unpei Yokoyama was the very first Japanese film star, making his first screen appearance in Japan’s first official film - a 2 minute short of a robbery – made all the way back in 1899; at the peak of her fame and success legendary actress Setsuko Hara announced her retirement from films the following year, claiming she never enjoyed acting and only wanted to provide for her large family. Rumours persist over the real reason for her retirement, having never married she earned the nickname “The Eternal Virgin”. Setsuko stayed out of the public spotlight and refused all film offers and interviews until her death in 2015 at the age of 95. As one screen icon left the silver screen another made its appearance. Shintaro Katsu starred in several sword fighting films before earning legendary status as the former masseur and blind swordsman Zatoichi. The first of over two dozen films in the series introduces us to a cunning and highly-skilled swordsman, looked down upon for his blindness and revered for his prowess with the sword. Similar to “Yojimbo”, the blind man enters a town controlled by the yakuza, a nearby rival gang employs Hirate, a samurai suffering from tuberculosis who becomes friends with the blind swordsman as the two gangs square up for a final showdown. Both gangs build up the climactic battle between the blind Zatoichi and the dying Hirate. The old days of the honourable samurai were long gone, the samurai genre now preferred rule-breaking ronin challenging the system. Having finished the exhausting Human Condition trilogy the year before, Masaki Kobayashi first made “Inheritance”, the story of a dying businessman (So Yamamura) wanting to give two thirds of his wealth to his three illegitimate children. The lure of ¥200 million is too much for his wife and business associates, all of them double-crossing one another to get their hands on the loot. His secretary Yasuko (Keiko Kishi) gets caught up in his twisted games but can she find a way out? An engrossing noirish tale of double-crossing greed and the corrosive effects of money. A different sort of samurai film and Tatsuya Nakadai’s personal favourite of all his films, “Seppuku” won the Jury Prize at Cannes. Masaki Kobayashi’s disdain for the military dictatorship is reworked into 1630s Japan, a scraggly ronin arrives at the gate of the famed Iyi School requesting permission to commit seppuku within its grounds, he learns of another ronin who tried the same trick with a bamboo sword looking for money, forced to disembowel himself with a blunt sword that wouldn’t even cut through tofu. As the ronin prepares himself he requests another retainer of the house to be his second, the retainer turns out to be ill, the same follows with the other two requests, this ronin has more up his sleeve. Tatsuya Nakadai’s distinctive voice was in imitation of a kabuki narrator, relating his story to the intrigued members of the Iyi School and how it ties in with the three sick samurai.  Tsugomo has a story to tell

Tearing down the samurai code of honour from the inside, “Seppuku” is often labelled one of the best samurai films ever made, quite a surprise for a chanbara with more talking than action. The film’s swordplay is highly regarded; instead of bamboo swords covered in silver leaf, metal swords were used to portray the weight of each slash onscreen. The sweeping camera and windy location of Tsugomo’s duel with the Master Swordsman takes us out of the inner courtyard, backed by an evocative score by legendary Toru Takemitsu The novels of Fumiko Hayashi were much loved by Mikio Naruse, this time he adapted Fumiko’s autobiography to the silver screen. Hideko Takamine plays the writer with a hint of melancholy, she dreams of being a successful writer and finding real love but winds up disappointed several times along her path to fame. She takes demeaning jobs in bars to keep her head above water, she gets married and cheated on, after her early poems get published she joins a literary group, she also tries to care for her mother (played by Kinuyo Tanaka). The only man she really can trust is an old friend played by Daisuke Kato, an unattractive and kind widower secretly holding a candle for her. Compared to other “rags to riches” story this one doesn’t have a feel-good happy ending, even after Fumiko makes it she still bears some scars of the grinding experience. Such a creative boon for the director, it would be the last time Naruse adapted a Fumiko Hayashi novel. Director Kon Ichikawa directed two movies based on outsiders: “The Outcast” deals with a member of the “burakumin” , the lowest caste in Japanese society (think “Untouchables” in India) trying to hide his past from a judgemental society. The more interesting film is based on a gimmick: first-time parents as seen through the eyes of a two year old. “Being Two isn’t Easy” covers roughly 12 months in the life of a small Japanese family living in a cramped Tokyo apartment. All the fears of raising a child for the first time are here, whether the parents feel they’re doing the “right thing”, sometimes we get voice-over narration from the toddler unhappy with his parents, there’s a hint of “Le Petit Prince” about the flaws of adulthood from a child’s perspective. Being somewhat of a gimmick the film’s short running time ensures it doesn’t drag, a surprise winner of “Japanese film of the year” considering the tough competition that year. To the north of Tokyo lies Kawaguchi, an industrial town filled with factories undergoing post-war decline and automation. The heroine of the story Jun wants to enroll in high school but her family’s poor, her dad’s hiding in alcohol after losing his factory job while her younger brother is perennially in trouble. Another subplot is a North Korean family’s hopes of being repatriated to the country along with the discrimination experienced by Koreans in Japan. A screenplay co-written by Shohei Imamura, the town isn’t depicted as harshly decaying as it could’ve been, unions are seen as a benefit to workers while the old habits embodied by Jun’s father still persist. A pretty entertaining film with a socialist angle for triumphing through poverty. Compared to other directors Hiroshi Teshigahara came from an upper class background, the son of a renowned Ikebana master, he was fortunate to collaborate with hugely talented individuals for his debut feature film “Pitfall”, a screenplay by existentialist novelist Kobo Abe and avant-garde composer Toru Takemitsu. Based on a television play called “Purgatory”, the story is set in the mining town from hell, one miner gets murdered by a man in a white suit, joining the latter’s earlier victims in a surreal afterlife. Equal parts absurd, unpredictable and unsettling, it was the start of four fruitful collaborations between director and screenwriter. Another funny post-war commentary on changing social attitudes, majority of the film takes place in a small apartment, based on a screenplay by Kaneto Shindo. The parents are quickly moving all the fancy stuff out of sight before guests arrive, turns out their son has been embezzling hundreds of thousands to the shock and surprise of the contrite parents, once the guests go the parents know fully well their son’s behaviour, they encourage it as long as he doesn’t go too far. Their daughter is currently the mistress of a famous novelist who paid for the appartment the family currently lives in. The cynical family attitude towards love and money can be explained by their horrific past living in a small shack eating gruel everyday, something none of them want to go back to, it’s the most poignant part of a cynical and very good film.  The confined apartment feels claustrophobic during this argument Yasujiro Ozu likened himself to a “tofu maker”, making the same films with minor variations. “An Autumn Afternoon” bears great similarity to his 1949 film “Late Spring”, an elderly widower also played by Chishu Ryu lives with his unmarried daughter Michiko (Shima Iwashita) who takes care of him. His old school friends believe it’s time she got married but the old man is worried about being alone. On the other hand his son Koichi is finding married life and working as a salaryman not all it’s cracked up to be, his wife Akiko holds the purse strings extra tight when he wants to buy golf clubs. If you love the slow-paced films of Yasujiro Ozu you will love this film. Sadly this turned out to be the final film by Ozu: the following year he was diagnosed with cancer and died on his 60th birthday. Revered for his insights into romance and life he never married, instead he lived with his mother until her death. |

|

|

|

Post by Woland on Mar 26, 2021 15:08:05 GMT -5

1963

1963 saw the number of Japanese movies fall further, ticket prices rise and cinema attendance numbers fall even further. Japan was also preparing to host the Olympic Games the following year, a chance for international redemption; Tokyo was scheduled to host the 1940 Olympics but the Japanese invasion of China saw that honour given to Helsinki instead (the Olympics were eventually cancelled that year due to WW II).

Construction work on Tokyo Highway, December 1963

In 1962 23 year old Kenichie Horie became the first Japanese person to sail across the Pacific Ocean, his incredible adventure was turned into a comedic tale of a disaffected twenty-something wanting to escape a rigid society. An actor known for representing youthful rebellion, Yujiro Ishihara was cast in the lead role, his traditional parents played by Masayuki Mori and Kinuyo Tanaka, renowned stars of the 40s and 50s. Because endless views of open ocean would’ve been too repetitive, flashbacks are used to provide a glimpse into Kenichie’s life on land, the comedy lies in Kenichie’s inexperience as he battles the waves and his sanity for three months all the way to San Francisco, writing an absurdly long checklist of “essentials” for the journey, including a ton of books, canned fruit and straw hats. Noted as the first Japanese film to be partly shot on location in the United States, it was nominated for a Golden Globe.

The "mermaid" yacht on the Pacific Ocean

Judging by the opening scene, the full title “Bushido: Cruel Code of the Samurai” looks like it belongs to the wrong movie: a young salaryman (action star Kinnosuke Nakamura) finds his fiancée in hospital after a suicide attempt. He flicks through a book on his samurai family’s history, the story moves back to the 1600s, his ancestor (also played by Kinnosuke) isn’t a swaggering hero of glorious battles, instead forced to sacrifice his own personal feelings for the greater Bushido good. With each descendant the same story of an ancestor (all played by Kinnosuke) violating his own conscience out of loyalty to his vindictive Lord, by the time Kinnosuke is playing his 8th character the message has already been rammed home, none of the family ancestors are explored in great depth, all are tools of their masters to be used and abused at their whim. Once we return to the modern day, the salaryman realises all too well the corporate world has more in common with the samurai class system than at first glance.

One cruel punishment meted out to retainers by a sadistic Lord