|

|

Post by Woland on Jan 1, 2021 14:57:15 GMT -5

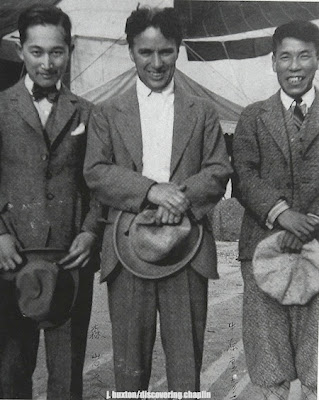

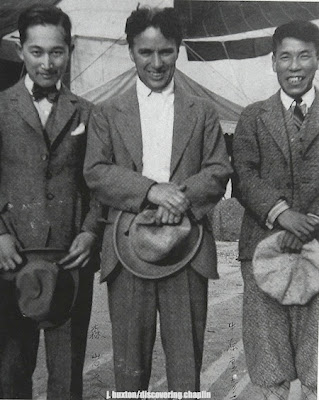

Scholars and critics demand every national cinema must have a Golden Age to celebrate its peak and a New Wave to radically break with tradition. Ascribing a precise timeline to both periods isn’t easy thanks to the overlap between periods. The 1950s is sometimes considered the peak of Japanese cinema, a slew of talented directors and actors hitting their artistic stride after the damaging post-war years, while the New Wave can stretch from the late 50s to the early 70s. Some even consider the 1930s to be a Golden Age in Japanese Cinema. To restrict the Golden Age to the 1950s cuts off similar films made in the early 60s by those old-school directors and ignores the early signs of an upcoming New Wave in the late 50s, when a generation of young directors looked to break with their predecessors and tackle taboo subjects with experimental narratives. 1965 seemed an appropriate cut-off point as certain genres and individuals revered in the 50s either passed away or fell out of fashion. I will start off with a not-so-brief look at whatever remains of pre-1950 Japanese Cinema before following the years in question. Tokyo, 1897 Like much of the rest of the world Japan was introduced to cinema at the turn of the century. Unlike in America or France where the moving pictures were considered an extension of photography, cinema was considered an extension of traditional theatre in Japan, exemplified by the importance of a narrator (benshi) who commented on the action and provided dialogue for the onscreen actors. Whereas live-narration in the US died out in the 1910s, a benshi would continue to describe onscreen action in Japanese film theatres until the early 1930s. In Bunraku puppet theatre the narrator plays a more important role in describing the action, compared to Kabuki or Noh. This video gives a brief overview of Bunraku, notice how the puppeteers remain silent at all times. Thanks to a disregard for film preservation, government repression, wartime bombings and the passage of time, it’s estimated 90% of Japanese films made before 1945 are lost forever, in some cases the surviving films are missing important scenes and reels. Compounding the headache for film historians and archivists that figure is slightly higher for pre-1920 Japanese cinema. To give one a glimpse into the 1910s here is a still photo from “The 47 Ronin” (1910), a legendary 18th century event turned into dozens of plays and films, directed by pioneering Japanese director Shozo Makino, sometimes called the D.W Griffith of Japanese Cinema: ![]()  The 47 Ronin (1910) Shozo Makino In the mid 1910s foreign films were becoming more popular, influencing a new generation of budding filmmakers and delighting audiences who felt Japanese films were inferior to Western imports. Yasujiro Ozu claimed the 1916 film “Civilisation” made him want to become a film director, while the 1919 screening of D.W Griffith’s “Intolerance” was a great success. The 1920s saw several writers, technicians and directors return to Japan from study abroad as Hollywood silent films such as Sunrise, The Marriage Circle, Orphans of the Storm, The Kid and Seventh Heaven enraptured Japanese audiences.  Mori Iwao, Charlie Chaplin and Ushihara Kiyohiko in 1926 on the set of “The Circus”. Iwao would become executive producer at Toho Studios, Kiyohiko became a silent film director. Whether or not “Western” influences on domestic cinema are good or bad is a rather tedious debate often played out around the rest of the world. As always producers and studios pick and choose the appealing aspects of American films, hoping to sell tickets and fill their coffers. All that changed after The Great Kanto earthquake of 1923 devastated Japan and its film industry. It struck 25 miles south of Tokyo, devastating the city and the nearby port city Yokohama, killing over 100,000 people.  Nihonbashi, Tokyo after the Earthquake Due to the severe damage in Tokyo, productions of period dramas (jidaigeki) were moved to the more conservative, old-fashioned Kyoto, while contemporary films (gendaigeki) remained in the modernising and Westernised Tokyo. The earthquake is sometimes claimed to have destroyed the traditional, forced an embrace of modernity. Whatever the case, Japan and its film industry recovered so fast that in 1928 Japan was making more movies than any other country in the world, while Japanese audiences flocked to the cinema to consume domestic and foreign films. The most eye-opening fusion of Japanese and foreign influences is “A Page of Madness” (1926), directed by Teinosuke Kinugasa with the future Nobel laureate Yasunari Kawabata listed as a screenwriter.

![]()  Considered lost for 40 years until a negative was discovered in a shed, the story of a man taking a job at an insane asylum to free his wife is transformed by expressionistic lighting, rapid cuts, odd angles and silver-painted sets to create a startling visual feast for the eyes. The influence of Dr. Caligari can be seen in the lighting and storyline, while the absence of intertitles evokes Murnau’s “Last Laugh”, a film Kinguasa loved. At just under 80 minutes it can be overwhelming in its experimentation. While “A Page of Madness” remains an anomaly within Kinugasa’s own oeuvre, his film “Crossroads” (1928) made two years later was the first major Japanese film to be shown in Europe. The tale of a man falling for a courtesan is told in a far more conventional narrative, the visual effects used to enhance the storyline and depict the psychological state of the characters, more impressionistic than expressionistic. If the lack of soundtrack is disconcerting, Japanese silent films would’ve been accompanied by music and a narrator (benshi) describing the on-screen action and providing dialogue for all the characters. A carryover from Japanese theatre, it was a highly skilled and difficult job (just imagine the poor soul who had to narrate over “Page of Madness”). To give you a clear idea of how that would’ve sounded, this 1931 film “Jirokichi the Rat” was screened with traditional Japanese instruments and a narrator describing the action. Somewhat overwhelming at first, the Robin Hood-esque tale helps one to appreciate the skill involved in live narration, the switching of tones and dialects. The movie itself is the only surviving silent by Daisuke Ito who loved pan-shots, about 20 minutes of the film is still missing. The moment talkies appeared with “A Neighbour’s Wife and Mine” in 1931 the narrator’s days were numbered, although silent films persisted for a few more years. Yasujiro Ozu’s best silent film “I Was Born, But..” (1932) focuses on two school boys who find out their father is a brown noser at work. Ozu’s themes of family relationships and his decades-long collaboration with Chishu Ryu are all on display here with a touch of humour and darkness, superior to the colour remake “Good Morning” made in the late 50s. Sometimes the 30s is considered the first “Golden Age” of Japanese cinema, the 3 big film companies (Shochiku, Toho and Nikkatsu) had grown over the previous two decades while a handful of smaller companies would survive until they were forced to merge with the 3 majors by wartime government decree. While Toho had the more famous actors Shochiku arguably had the better directors in their roster.  Japan Film Directors Society, 1936 The 1930s also saw a number of budding assistant directors who would learn from every other department and later bloom into great directors themselves in the future. The prolific director Mikio Naruse made a Brechtian drama “Avalance” in 1937 with Ishiro Honda as 2nd assistant director and a certain Akira Kurosawa as 3rd. Kurosawa served as assistant director for Kajiro Yamamoto for 17 films before he began directing his own films, the latter acted as mentor for the future legend. Akira Kurosawa with his mentor

One of the most well-regarded directors of the 30s, Hiroshi Shimizu began his directorial career at 21, in the 30s he utilised on-location shooting to great effect in “Japanese Girls at the Harbour” (1933), while his crowd-pleasing films about children in the late 30s managed to evade harsh censorship dogging other films. Almost forgotten until his work was rediscovered ten years ago, in the 30s Kenji Mizoguchi called him a genius. Perhaps his best known film “Arigato-san” (1936) is a deceptively simple story about a kind-hearted bus driver and his passengers travelling through the countryside. Mizoguchi himself is considered part of the Holy Trinity of Japanese directors, though he maintains he didn’t begin making serious films until “Osaka Elegy” in 1936. You can see glimpses of the trademarks he’d use in his later masterpieces: long takes, fluid tracking shots, focus on the self-sacrificing nature of women in society. In the story a young womanbecomes her boss’ mistress to save her family from financial ruin. Over the course of the film she tries to do the right thing for herself and her family. Mizoguchi was called a “feminist” director for always directing films about the plight of women, though Mizoguchi maintains it was the studio’s insistence that he make films about heroines. He would jokingly say working with actresses would put a lid on his quarrelsome nature as he “couldn’t slug an actress”. Sadao Yamanaka directed 22 films in his lifetime of which 3 survive, mainly focused on jidaigeki with a twist. “The Million Ryo Pot” (1935) is a comedic farce centred on a secret treasure, while his final film “Humanity and Paper Balloons” was released on the same day he was drafted into the Imperial Army. Unlike his close friend Ozu who also joined the army, Yamanaka did not survive the war, dying in a hospital in Manchuria at just 28 years old. Recognised for his elegant directorial style and humanistic view of history, we can only guess at the sort of success he would’ve achieved had he survived the war. ok.ru/video/2041513708142The invasion of China saw the government launch further restrictions and censorship against films, directors now had to use subjects to highlight positive Japanese qualities. Even foreign films were subject to censorship: “All Quiet on the Western Front” was heavily cut while “La Grande Illusion” was sent back to France. Not everyone navigated these new rules successfully: documentary maker Fumio Kamei has the distinction of being censored by the Japanese Government during the war and by the Occupying Forces after the war. “Fighting Soldiers” (1939) follows a Japanese infantry regiment during the invasion of China. Kenji Mizoguchi moved into historical dramas to avoid commenting on the present, “Story of the Last Chrysanthemum” (1939) is often praised as his first real masterpiece, a melodrama devoid of close-ups with several long-takes (average shot length is 1 minute). The son of a legendary kabuki actor struggles to live up to his father’s expectations: If the mildly propagandistic “Five Scouts” (1938) praised loyalty to the Emperor and promoted Japanese qualities, the complete defeat of 1945 and subsequent occupation by the Allied Forces meant a repudiation of nationalistic-leaning films. Instead Japanese films had to look forward to a peaceful future without criticising the Occupation forces. As part of a de-militarisation pre-war prints were seized and burned, the Japanese Government had to punish so-called “war criminals” within the industry (most charges were later dropped) and a new censorship took place prohibiting anything even touching militarism (period dramas were out), any potential nationalistic symbols (including bowing and Mount Fuji) and a refusal to show any allied war damage, Gis were not to be shown onscreen either, quite an issue for directors wanting to film on-location.  Tokyo, 1946 Films which promoted a peaceful path forward for Japan and a rejection of its militarist path were preferred. “Morning for the Osone Family” (1946) depicts the changing fortunes of a Japanese family during the war, one militaristic uncle an unsubtle symbol of Japan’s past as the film progresses and the war turns against Japan. The opening scene could’ve been lifted straight out of Hollywood, while later in the movie when Japan surrenders there is no mention of the Atomic Bomb. “Ball at the Anjo House” (1947) wears its pro-Western sympathies on its sleeve, borrowing from Chekhov’s “Cherry Orchard” while featuring European paintings and music from Chopin. Directed by Kozaburo Yoshimura with future director Kineto Shindo as screenwriter, the film follows a formerly noble Japanese family about to lose their mansion and way of life to the rising middle class, they throw a lavish ball as a final send-off. Somewhat melodramatic in places with lots of subplots it looks to a bright future ahead, just like Kurosawa’s “No Regrets for our Youth” (1946) it also features screen icon Setsuko Hara. Despite these restrictions and the necessity of making “American” films, several Japanese directors preferred working under the Occupying forces compared to the wartime Military Government. Occupation would officially end in 1952, in the meantime Japanese directors were beginning to find their own personal voice as the 40s drew to a close. The best of Kurosawa’s early films “Drunken Angel” features his first collaboration with legendary actor Toshiro Mifune. Kurosawa managed to sneak a couple criticisms of the American Occupation into the film, most notably the bombed out sets. In this scene Mifune squares off with fellow Kurosawa-stalwart Takashi Shimura. Yasujiro Ozu served in the Army and managed to avoid making propaganda films for the government. Upon his return to Japan he began making films, catching commercial success with the first in the “Noriko Trilogy” known as “Late Spring” (1949). The story of Noriko (Setsuko Hara) not wanting to marry in order to stay with her widowed father (Chishu Ryu) is considered one of his greatest films, this justly celebrated scene showcases the universality of Ozu’s cinema. With the end of the 40s Japanese Cinema was about to embark on its most celebrated era, Japanese cinema of the early 50s would put Japan on the cinematic map, win international prizes and influence filmmakers around the world for decades to come.  To be continued.... |

|

|

|

Post by andrew on Jan 2, 2021 10:52:52 GMT -5

Kurosawa would butt heads with Hollywood in the 1960s with his involvement with Runaway Train and Tora! Tora! Tora!. He was a bit of a control freak along the lines of Ridley Scott (aka to those who worked under him as "Ridley is God"). He caused so many delays in the pre-prduction of Runaway Train that he requested a delay in shooting due to his own mental exhaustion. His script for the Japanese half of the Tora! Tora! Tora! production was longer than the intended final production, which was supposed to include, you know, the American side of the story as well. He was fired after only a few weeks. His nearly life-size set of the Battleship Nagato, built on a beach and over 700 feet long, and featured in the opening of the film, on its own entirely blew the budget of the production.

|

|

|

|

Post by Abraham on Jan 2, 2021 20:21:57 GMT -5

Fascinating thread. I don't have much to contribute, but I do enjoy reading them. That scene with the widower and his daughter bride was really moving.

|

|

|

|

Post by Woland on Jan 10, 2021 7:24:21 GMT -5

1950 - 1953

The early 50s saw the end of Allied Occupation as Japanese society grappled with rebuilding the country and its future cultural direction, the country needed to rebuild its international reputation while America needed an ally during the Cold War. On the cinematic front Japanese audiences were more interested in the present, international audiences were more captivated by an image of Japanese exoticism in period dramas (jidaigeki). Several important and outstanding films were made in this period, international reputations were forged by seasoned veterans and a couple notable debuts were made. Signing of the Treaty of San Francisco, 1951

In the late 40s Kenji Mizoguchi felt uncomfortable in the post-war period, he continued to make films about long-suffering women without the same conviction, a trend which continued into 1950 with “Madame Yuki”, a tale of a formerly noble woman who can’t leave her abusive husband. At the start of the film a new maid is starstruck at the prospect of working for such a refined woman until she discovers Madame Yuki’s inner turmoil and flaws. Something of a transition work in Mizoguchi’s filmography, some of his famed tracking shots are on display near the end of the film, this scene shows Yuki’s lonely walk and disappearance act. When one thinks of famous Japanese directors Tadashi Imai rarely gets a mention, nowadays derided as sentimental and simplistic, his films won the “Film of the Year” award 5 times by Kinema Junpo magazine, a mark of his popularity. His first success “Till We Meet Again” is treated as a historical footnote today, back in 1950 it was relevant and touching to an audience still recovering from the war. A straightforward war-time romance with touches of sentimentality, it slowly develops the romance between Saburo (Eiji Okada) and Keiko (Yoshiko Kuga), they cross paths on the train, they slowly flirt, discuss their careers and interests, look at baby photos of one another, they even share several on-screen kisses (kissing was verboten in Japanese films until 1947). Their time together is limited thanks to the on-going war and the air-raids on Tokyo, he’s a student discussing literature and translations with his friends while his older brother berates him for “not concentrating on the war”, she illustrates war posters as the two come to accept he’s going to be drafted into the war effort. If you’ve seen any star-crossed lovers movie this will come across as rather pedestrian, it was set to be Japan’s entry at the Venice Film Festival but they couldn’t subtitle it fast enough, instead something else was sent.

![]()  Eiji Okada and Yoshiko Kuga in "Till We Meet Again"

Much praise has been lavished upon “Rashomon” for its importance to world cinema, for winning the Golden Lion at Venice to kickstart European and American interest in Japanese cinema, for earning an honorary Oscar for “Most Outstanding Foreign Language Film”, for the conflictingly unreliable narrative, the ingenious cinematography by Kazuo Miyagawa. Surprisingly upon first release in Japan the critics disliked it, a return to Japanese theatres after conquering Venice was met with disappointment by Japanese audiences surprised by its international success. Some of Rashomon’s poor reception at home can be explained by its historical setting since period films were too closely tied to militarism in the minds of Japanese audiences and American censors. Another possibility is the so-called “kimono effect”: Japanese studio bosses – in particular Daiei - wanted to portray an exotic image of Japan to foreign audiences through period dramas, a successful tactic over the following years. As for the film itself, Kurosawa borrowed two short stories from modernist writer Ryunosuke Akutagawa telling the story of a robbery and a murder from 4 conflicting viewpoints: the bandit Tajomaru (Toshiro Mifune), the woodcutter (Takashi Shimura), the bride (Machiko Kyo) and the samurai’s ghost (Masayuki Mori). While I cannot doubt its importance, I feel Kurosawa made better movies over the next 15 years. To increase light into the dark forest cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa “borrowed” a mirror with some leaves to soften the glare on the actor’s faces. This scene of the woodcutter’s entrance into the forest and discovering the crime showcases the tracking shots and lighting that would make Miyagawa Japan’s greatest cinematographer.

In 1951 audiences were greeted by Japan’s first colour film “Carmen Comes Home”. Due to renovation works at her Tokyo-based venue, the young and famous artist Okin, or “Lily Carmen” returns to her home village to much fanfare from the locals, until they discover what her “art” entails. www.facebook.com/watch/?v=382160779487437Shot on location in the foothills of mount Asama (an active volcano), the Fujicolour process contrasts the stylish fashion of the young Tokyo stars compared to the mundane clothes of the village locals. As a precaution a black and white version was filmed too, the costly colour printing process meant most theatres screened the black and white version. As a comedy it doesn’t take sides in the urban/rural divide, Hideko Takamine has a lot of fun in the lead role with Chishu Ryu taking a break from serious family dramas. In this scene the blind music teacher tries to perform his composition to the rest of the village, the locals too distracted by Carmen and her friend. The tension between traditional and modern was on full display in Kenji Mizoguchi’s “Lady from Musashino”. At the start the parents take in their daughter and her husband during the air raids (the atomic bomb is also mentioned), the deaths of the parents aren’t shown but their traditional values hang over their daughter Michiko for the rest of the film. In contrast her husband Akiyama is a modern opportunist, teaching Stendhal to students and having an affair thanks to the 1947 decriminalisation of adultery law in Japan. The one benefit of the war is the return of Michiko’s cousin Tsutomu from a POW camp, he’s very interested in the local history of Musashino (a pleasant town on the outskirts of the ever-expanding Tokyo) and takes romantic interest in Michiko. She refuses his advances as Japan’s post-war identity and future direction is called into question. Old-fashioned Michiko and her cousin Tsutomu

Heading to Kyoto for a tale of two sisters, “Clothes of Deception” was directed by Kozaburo Yoshimura with a screenplay written by Kaneto Shindo. This time the traditional/modern question is centred around money and love. Kiku is a former geisha whose home was paid for by her wealthy patron, her two daughters are on different career paths with different views of romance: Kimicho is a geisha happy to earn as much money from each patron as she can, while Taeko works in the tourist office looking to get married. As the story progresses Kimicho takes centre stage, scolding her mother for mortgaging the house to aid her patron’s son, she discards one patron at a bar and starts dancing with another, after he apologises for stepping on her toes she says she’s happy to “have his weight on her”. She’s not all greed and cynicism though, she tries to help her sister get married and move out of Kyoto, the problem is Taeko’s fiancé is meant to inherit the family business and his mother doesn’t want him marrying into a “lower” family. Many films of the time portray the tough life of a geisha, in this one Kimicho takes her fate all in her stride as she tries to do some good. ok.ru/video/2125588531822After the disappointing experience of making “Munekata sisters” the previous year, Yasujiro Ozu returned to the story of an unmarried woman in a modernising Tokyo with “Early Summer”. Setsuko Hara’s lack of a husband is a concern for her parents and her married brother, they try to set her up with a 40 year old man but she’s an independent woman free to make her own decisions. Usually taken as part two of the unofficial “Noriko trilogy”, Ozu was more interested in showing a life cycle in this film than sticking to a conventional narrative. In his previous film he found it difficult adapting a novel to the big screen, he was much more comfortable working from an original screenplay with his writing partner Kogo Noda. Late in the film after Setsuko Hara has made her decision, she visits the beach with her sister-in-law. The shot of the two walking up the dune is one of the few times Ozu used a crane shot, as opposed to his usual low-angle shots. Mikio Naruse is sometimes grouped together with Ozu on thematic and stylistic grounds, though they are more different than at first glance. Ozu prefers middle class families while Naruse goes for the lower-middle class, Ozu’s films have a slower pace with more rigid acting, Naruse would make two or three films a year and rarely gave his actors directions. His reputation was boosted in the 50s with several films focused on the lower-middle class, his first major success in the 50s was “Meshi” (Repast), one of his first adaptations of a Fumiko Hayashi novel. Setsuko Hara moved from Tokyo to Osaka to be with her businessman husband, she’s worn down by cooking and cleaning for her inconsiderate husband. Her husband’s niece arrives at the home having run away from her parents, he gives his niece all the attention Setsuko wants. As the story unfolds it becomes less about personality and more about the post-war situation and lack of opportunities. A slow-burning film rich with insight, it revitalised the shomin-geki genre of struggling lower-middle class families. ok.ru/video/1671602571886In 1952 the Allied Occupation ended, Kurosawa’s long-suppressed film “Men who tread on the Tiger’s Tail” was released. The year before his adaptation of Dostoevsky’s “Idiot” was harshly cut by the studio. To scale back his ambitions Kurosawa turned to the story of the ordinary bureaucrat Kanji Watanabe who inadvertently discovers he has terminal cancer in “Ikiru” and sets out to accomplish one last meaningful deed before he dies. Some audiences are shocked by the doctor not informing Kanji of his condition but that was common practice in those days; doctors believed telling a patient they have stomach cancer would only aggravate the disease. Kanji goes through several different stages of dealing with his diagnosis, including a lengthy drinking session until he finally gets an idea. Personally I find the movie too sentimental and drawn out, the final third of the movie goes into flashback mode to heighten the emotional impact of the “swing scene”:

As one director was hitting his stride another was making his debut film, Masaki Kobayashi was second-cousin to actress Kinuyo Tanaka and served as assistant director on “Carmen Comes Home” the year before. “Youth of the Son” is the complete opposite of everything he’d make afterwards, closer to the films of his mentor Keisuke Kinoshita. Warm and sometimes goofy comedy about two brothers approaching adulthood, one discovers girls while the other gets into fights. The American influence is quite strong in this film: In the opening scene one boy sings “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon”, later in the film a group of school kids sing “happy birthday” in english, when the teenagers go on a date she wears pearls and he wears an oversized suit.

That same year Kenji Mizoguchi was allowed to make his dream film “The Life of Oharu”, based on the 17th century novel “Life of an Amorous Woman” by Ihara Saikaku. Kinuyo Tanaka plays the titular character as an old woman reflecting on her life and loves, her fall from lady-in-waiting and attempts to escape her situation thwarted. A bleak film enlivened by Mizoguchi’s fabled long takes and Tanaka’s stunning central performance, the film earned Mizoguchi the International prize at Venice, announcing him as a major figure in Japanese and world cinema.

The third film by Kaneto Shindo was sponsored by the Teachers Union of Japan, a narratively light tale of a school teacher returning to her hometown Hiroshima four years after the bomb. Focusing on the human stories of the bombing and its aftermath, the film was criticised by its sponsors for not being critical enough of both sides and not showing the true horrors of the atomic bomb, a later documentary “Hiroshima” was commissioned to give a more graphic view of events. This scene from “Children of Hiroshima” gives a fictional and disturbing account of the moment “Little Boy” was dropped:

The beginning of 1953 saw a war film “Tower of Lilies” based on the true story of the Himeyuri students a.k.a. “Lily Corps”, a group of 222 students and 18 teachers drafted into a nursing unit during the Battle of Okinawa (only a dozen survived). At the start of the film the teenage girls are upbeat and cheerful until forced to stay in a shelter, treating the sick and wounded without enough food or supplies. The government declares they’re winning the battle, the situation on the ground suggests otherwise. As the war turns against Japan the bombing raids increase, students get killed and a relocation is planned with the Americans closing in, the Japanese government’s tune changes from “we’re winning” to “we’re doing better than expected”. The story has its cheerful moments, the camaraderie between students and teachers in a life-and-death situation keeps the viewer interested right up to the bleak end. ok.ru/video/1604335897198

Away from the battlefields, several films about women were made but only one was directed by a female. Famous actress Kinuyo Tanaka wasn’t the first female director in Japan but she managed to direct 5 more films after her debut “Love Letter”. Masayuki Mori has found a job writing love letters in english for Japanese girls to American soldiers, one day he discovers his ex requesting a love letter. Mori has drifted through life ever since she left, he wants and needs her but can’t forgive her past. It has its melodramatic moments but as a directorial debut it’s fine. ok.ru/video/1617337387630

On the international front 1953 was a stellar year for Japanese cinema, beginning with Teinosuke Kinugasa’s “Gate of Hell”. Daiei studio imported Eastmancolor from America to export the first Japanese colour film, they wanted to show off 12th century Japan in vibrant costumes and extravagant colours. “Gate of Hell” won top prize at the Cannes Film Festival, one Oscar for costume design and another honorary Oscar for “best foreign language film”. Based on a play the film kicks off with the Heiji Rebellion of 1159, Morito (Kazuo Hasegawa) saves the life of lady-in-waiting Kesa (Machiko Ryo). From that point on the movie becomes a straightforward tale of obsession and desire, the provincial samurai Morito wants Kesa but she’s already married to Wataru (Isao Yamagata) a samurai in the imperial guard. Judging by the start you can see why the cinematography and costumes are so lauded.

Thanks to his success at Venice the previous year, Kenji Mizoguchi was offered complete artistic freedom and a large budget by Daiei studios, The resulting film was a period drama based on short stories by Ueda Akinari called “Ugetsu Monogatari” a.k.a. Tales of Moonlight and Rain. Set in late 16th century during the Japanese civil wars, Genjuro (Masayuki Mori) dreams of getting rich through pottery to give his wife Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka) lots of fancy kimonos, his hapless neighbour Tobei (Eitaro Ozawa) dreams of being a samurai to the annoyance of his wife Ohama (Mitsuko Mito). Initially the story was meant to be a clear and lucid adaptation of the tales, Mizoguchi’s perfectionism saw multiple rewrites as the anti-war message of the stories took precedence, the studio also asked for a more optimistic ending as Tobei’s storyline becomes secondary to Genjuro’s. In this ethereal scene the four of them (plus little Genichi) are travelling by boat to avoid Shibata’s cruel army, they encounter a bad omen which forces Miyagi and Genichi to go it alone, while the other three head to a nearby village to sell their wares, promising to meet up later. This scene was filmed in a studio pool, assistant directors pushing the boat along the “lake”. For the look of the film Mizoguchi wanted the scenes to “unroll seamlessly like a scroll-painting”, he had worked with Kazuo Miyagawa on “Miss Oyu” (1951) and showed him several emaki scrolls for inspiration, Miyagawa estimates about 70% of the finished film utilises crane shots. For the visual look Mizoguchi wanted a subdued effect with very little contrast and delicate greys, similar to the Southern School of Chinese painting. This scene of Genjuro entering Kutsuki Mansion gives one an eerie feeling, combined with the Noh makeup of Lady Wakasa (Machiko Kyo). The gradual lighting of the mansion adds to the intrigue. The film won a Silver Lion at the Venice Film festival, cemented Mizoguchi’s place as a great director and further popularised Japanese cinema in Europe and America. Often featured on “Greatest of all time” lists, it still plays second shamisen to another Japanese masterpiece made the same year.

Film poster

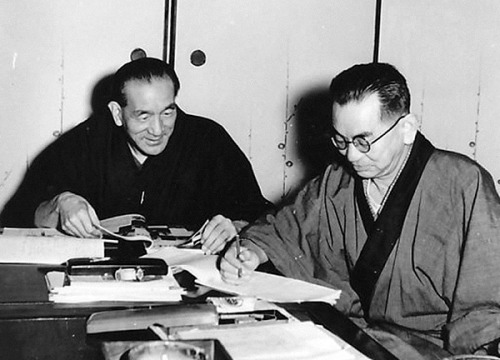

The best known and most cherished film by Yasujiro Ozu, “Tokyo Story” wasn’t shown in America until the 60s as Japanese film exporters felt Ozu’s work was “too Japanese”, quite ironic when the movie was partly inspired by the 1937 Hollywood movie “Make Way for Tomorrow”. The story is a familiar one, two elderly parents (Chishu Ryu and Chieko Higashiyama) travel to Tokyo to see their adult children: paediatrician Koichi (So Yamamura) is married with two young boys; beautician Shige (Haruko Sugimura) is married; while their widowed daughter-in-law Noriko (Setsuko Hara) whose husband died in the war also lives in Tokyo. This scene early on shows Noriko arriving at Koichi’s house to greet her in-laws. Much has been made of Ozu’s insight into family relationships yet it was his screenwriting partner Kogo Noda who suggested the plot from “Make Way for Tomorrow”. The two of them had a peculiar routine when it came to writing screenplays, they would stay at a countryside inn trying to drink their way to inspiration, it would take a while before they got going but once in the groove they wrote quickly. Usually one finished script would take around 3 months and 100 bottles of sake, in Tokyo Story’s case it was 103 days and 43 bottles. Yasujiro Ozu and Kogo Noda

Not long after the parents arrive it becomes clear the adult children either can’t or don’t want to spend time with them. In this scene the grandfather has met up with a couple old friends still in Tokyo, they get drinking and discuss their sons along with the changing times. Among its many accolades, “Tokyo Story” was awarded “most original and imaginative film” by the BFI in 1958, Kinema Junpo magazine voted it greatest Japanese film of all time in 2009, three years later Sight and Sound magazine asked 300 directors to name the 10 greatest films of all time, “Tokyo Story” came first. Decades after its release it still moves audiences to tears through its simplicity.  Left to right, back row: Noriko (Setsuko Hara), Shige (Haruko Sugimura), Koichi (So Yamamura), Fumiko (Kuniko Miyake).

Left to right, front row: Isamu (Mitsuhiro Mori), Tomi (Chieko Higashiyama), Shukichi (Chishu Ryu), Minoru (Zen Murase).

The next four years in Japanese cinema would see larger budgets, larger audiences and more accolades. The mid 50s saw the Golden Age hit its peak even as signs of a New Wave were slowly forming, as younger audiences and directors opted for American influences over Japanese. It would also see the zenith of one of Japan’s greatest directors.

To be continued. |

|

|

|

Post by Woland on Jan 20, 2021 8:13:03 GMT -5

A slight change in format going forward, instead of writing in blocks of 4 years I shall give a year-by-year account for the rest. Easier to break down into manageable chunks.

1954

1954 has a strong claim to the greatest year in Japanese cinema, larger budgets allowed for more ambitious projects, international awards piled up and legends were born. Toho Studios was responsible for two films influential in different ways, both infused new ideas and techniques into old ideas borrowed from Hollywood.  Shooting Kyuzo’s introduction Instead of shooting in the studio Akira Kurosawa filmed “Seven Samurai” on location for authenticity, the film ran so over schedule and over budget production was closed down twice. At the time it was the most expensive Japanese film ever made, albeit modest by Hollywood standards, the plot has been recycled by so many different times it is almost cliché: a poor desperate village hire 7 samurai to protect them from marauding bandits. Initially the film was meant to have six samurai, the writers suggested they take a leaf from Kurosawa’s earlier film “Men who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail”, including a more comedic character for the audience to identify with, hence Toshiro Mifune was given lots of room to improvise as Kikuchiyo.  Seven Samurai film poster Some viewers used to modern running times and rapid cuts dislike the 3+ hour running time spreading the action too thinly, ironically Toho studios cut the movie down to 50 minutes for American audiences for similar reasons. The additional subplots add social commentary to the film, the farmers need their crops protected at the start and are seen harvesting at the end. The movie was a big success in Japan and abroad, becoming the third highest grossing film of the year in Japan and winning a Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival. A perennial candidate for greatest film ever made, it is 3 hours of well-crafted, good entertainment. Akira Kurosawa loved American westerns and worshipped John Ford, over the following years his movies were remade into “The Magnificent Seven”, “Sholay”, “Fistful of Dollars” and “A Bug’s Life” among others. In March that year nuclear fallout from a H-bomb test contaminated a Japanese fishing vessel, all 23 crew members suffered radiation sickness, one died. In the early 50s monster movies were revitalised by King Kong’s re-release in 1952 and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms a year later (along with Ray Harryhausen’s stop motion effects). A producer at Toho combined these two elements into a screenplay that would create a genre known as kaiju (monster film)  Haruo Nakajima on the set of Godzilla. The full suit became so hot and uncomfortable it could only be worn in 2 minute spurts. Panned by the critics, lapped up by audiences, cut down and released in America with Raymond Burr awkwardly inserted into the frame, it spawned dozens of sequels in the longest running film franchise in history. A silly movie with dubious science and cardboard characters to match the man in the rubber monster suit, it succeeds in capturing the zeitgeist of Japanese fears on nuclear annihilation. Godzilla destroying Tokyo in miniature is equal parts crude and scary, the human terror and suffering in its aftermath reflects the fallout from Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The other Toshiro Mifune samurai flick released that year was another big budget offering from Toho. An historical adventure film loosely based on the life of legendary samurai Miyamoto Musashi, part one of the Samurai Trilogy was filmed in Eastman Color to show off the Japanese countryside, sets and costumes just like “Gate of Hell” the previous year. The 7th highest grossing film of the year in Japan, it follows the early life of a brash young man Takezo (Mifune), from his appearance on the losing side at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, seeking shelter with a widow and her daughter to escape local brigands, his time as a wanted outlaw and his encounter with the priest Takuan, Takezo is granted the name Miyamoto Musashi. Despite being overshadowed by “Seven Samurai”, it’s a brisk 90 minutes and the best of the trilogy. With so much competition it’s a surprise to discover the critics’ choice for Japanese film of the year, the touching anti-war drama “Twenty Four Eyes” based on a best-selling novel starring Hideko Takamine as Hisako Oishi, the new teacher of twelve 1st grade students on a remote Japanese island. At the start of the movie in 1928 her bicycle and modern suit shocks the locals isolated from the mainland, her students call her “Miss Pebble” as they slowly grow to love her.  “Miss Pebble” on her bicycle Five years later the students are now in 6th grade (the kids playing 1st graders replaced by their elder siblings), Japan readies for war and Hisako fears for the future. Her fiance is a naval engineer, she doesn’t want him or her boy students to die in the war, her principal tells her students must serve their country, one girl student drops out to help her mother at home, another wants to join a conservatory against her mother’s wishes. The film moves forward, Japan goes to war and surrenders, at the end of the film in 1946 the war has changed everything and everyone forever.  Hisako Oishi with her 1st grade students At times uncomfortably sentimental, it captured the sense of loss and regret over the wars in China and the Pacific, the pacifist message resonated with audiences struggling to cope with the after-effects of the wars. Beloved in its native Japan it scored a Golden Globe for Best Foreign Language film. Singing is a recurring theme throughout the movie, in the early sections the folk songs act as a celebration of childlike innocence, when the children graduate they sing for their lost youth, as the movie shifts ahead 5 years the 6th graders are singing, and as the war draws near patriotic songs and serving one’s country take precedent. At the end of the film singing is a coping mechanism, in remembrance of innocence lost. Mikio Naruse made one customary adaptation of his favourite novelist Fumiko Hayashi with “Late Chrysanthemums”, a decent story about the relationship between money and love, embodied by a former geisha turned moneylender and her two friends slightly resentful of her success and attitude. His other major film of the year was taken from the Yasunari Kawabata novel “Sound of the Mountain”, a family drama about an elderly father Shingo (So Yamamura) seeing both his children struggle with their respective marriages. His daughter Fusako (Chieko Nakakita) turns up at the home with her two young children, while his son Shuichi (Ken Uehara) is cheating on his doting wife Kikuko (Setsuko Hara). A study of family ties and changing attitudes towards marriage and family roles, Shingo appreciates his daughter-in-law’s docility and devotion and doesn’t like seeing his son behave coldly towards her. Shingo’s feelings aren’t selfless; he wants a grandson. Shingo’s own marriage with Yasuko (Teruko Nagaoka) wasn’t built on strong foundations; he loved her sister until she died and “settled” for Yasuko. With a storyline that could easily veer into cheap melodrama it’s a testament to the writing, acting and direction that “Sound of the Mountain” stays sincere and layered, Akira Kurosawa once described Naruse’s films as "like a great river with a calm surface and a raging current in its depths".  Setsuko Hara and So Yamamura with Mikio Naruse in the middle. On a lighter note, the under-seen movie “Somewhere Under the Broad Sky” depicts another family drama with each member trying to deal with their own problems: Ryoichi runs the family liquor store with his wife Hiroko struggling to fit in with her in-laws. His sister Yasuko is depressed about the limp she sustained during an air-raid, his younger brother Noboru is an idealistic student worried about his future prospects in an ultra-competitive Tokyo. A pleasant, upbeat film with flashes of humour without trying to make wider claims about the human condition (that would come later in Masaki Kobayashi’s directorial career).  Noboru and his friend Mitsui observing the Broad Sky. 1954 was a busy year for Kenji Mizoguchi. His contemporary drama “Woman of Rumour” covers a widow running a successful geisha house while her daughter recovers from a suicide attempt. His other period drama Chikamatsu Monogatari covers two people forced to run away together to escape damaging accusations. His best film was another period drama often lauded as one of the great works of world cinema “Sansho the Bailiff”.  Iconic image from the film. Based on a legendary folk tale, Tamaki (Kinuyo Tanaka) and her children Zushio and Anju are travelling to see her husband, a former governor exiled several years earlier because he wanted equality for peasants. Before his banishment he tells his son: "Without mercy, man is like a beast. Even if you are hard on yourself, be merciful to others." During the journey the mother is sold into prostitution on a distant island while the children are sold into slavery, working on the estate run by the cruel Sansho the Bailiff.  Sansho (standing), his son Taro on the left, Zushio and Anju as children in the bottom left corner. Life on the estate is harsh and demeaning, the other slaves take pity on the two quiet children reluctant to give their real names. It takes Taro, the more humane son of Sansho to learn of their exalted background, he tells them to bear the suffering for many years until they can escape to reunite with their parents. Ten years pass and Taro has left the estate, Anju (Kyoko Kagawa) retains hope of finding her mother but Zushio (Yoshiaki Hanayagi) has turned cruel under Sansho’s tutelage. From this point on the film becomes a moving story of the two children’s attempts to find their parents, scenes of poetic beauty and human suffering draw the viewer to the film’s moving climax. For the director the story has a personal resonance, Kenji Mizoguchi grew up in a lower-middle class family whose fortunes dropped rapidly, his sister was put up for adoption and later sold into geishadom, Mizoguchi’s father treated his mother and other sister brutally, something the director never forgot nor forgave. The film was another success story, Mizoguchi secured his reputation as a great director with another Silver Lion at Venice, American critics have called it one of the finest films ever made. An emotionally powerful story imbued with humane ideals and crafted with artistic flair thanks to Kazuo Miyagawa’s camerawork and Mizoguchi’s direction. |

|

|

|

Post by Woland on Jan 24, 2021 13:54:52 GMT -5

1955

Thanks to the previous two years of gilded masterworks 1955 had a tough act to follow. Akira Kurosawa’s forgettable “I Live in Fear” was a trite warning of nuclear annihilation, a theme he’d revisit at the end of his career. In part two of the Samurai trilogy Miyamoto Musashi has duelled his way to number 1 samurai in Japan, the top Kendo school in Japan disagree along with another young upstart. On top of that he’s got two women chasing after him, a step down from the first part with an interesting final duel. Kon Ichikawa was more interested in animation when he entered the movie business, his marriage to translator Natto Wada became a fruitful director/screenwriter partnership until her retirement from screenwriting. One minor success was an adaptation of Natsume Soseki’s novel “The Heart”;Nobuchi (Masayuki Mori) visits a dear friend’s grave every month, his wife isn’t allowed to join him, he doesn’t give reasons. He’s a morose intellectual unable to adjust to the changing world around him, a student called Hioki befriends him, they discuss ideas but Nobuchi is still reluctant to divulge his feelings. Flashbacks allow the viewer a glimpse into Nobuchi’s student days with his old friend Kaji, eventually Nobuchi summons the courage to tell Nioki the truth. Interesting psychological portrait. Nobuchi at his desk

Kenji Mizoguchi’s international success propelled him to unfamiliar territory, a Japan-Hong Kong co-production with Run Run Shaw, a colour film set in 8th century China “Princess Yang Kwei Fei” covers court intrigue with an Emperor still mourning his deceased wife. Often derided as feeble and forgettable, the movie lacks the cinematic flair of his previous works, the sets look constrained by budgetary requirements with Masayuki Mori unsure as the Emperor. According to Mizoguchi’s assistant director filming was very slow going, he believed Kenji worked best when he understood and connected with the material, Chinese history wasn’t his forte and the final film suffered. Tomu Uchida was a successful director in 30s Japan until he tried setting up his own company. Failing that he headed to the Manchuria Film Company, not returning to Japan until 1953. With help from fellow directors his comeback film “A Bloody Spear on Mount Fuji” was a huge critical and commercial success. A comic story of a samurai travelling to Edo with his two servants encountering several characters with their own storylines along the way: an orphaned boy tags along wanting to be a samurai; one shifty man is carrying an important bundle; a pilgrim; a policeman is searching for a notorious thief; a travelling musician with her young daughter. Over the course of the story all these storylines interlink with one another and find some sort of resolution, the servants Genta and Genpachi try to keep their master away from alcohol for his own good. In the opening scene all the main and secondary characters are introduced, we get a glimpse into the social structure through all their stories as the film progresses towards a stunning climax. Of all the films Mikio Naruse made, “Floating Clouds” is considered his magnum opus. The tale of a lonely woman (Hideko Takamine) trying to rebuild her life in war-torn Tokyo. In war-time Indo-China she had an affair with a married man (Masayuki Mori), back home they can’t reconcile their past happiness to their current despair. Both find other ways and other partners to cope with the fact neither of them are suited to prosper in this new hyper-competitive Tokyo. A huge success in its own country, it was voted 3rd greatest Japanese film of all time, a measure of how well it captured the mood of its time. Masayuki Mori and Hideko Takamine

|

|

|

|

Post by Woland on Jan 28, 2021 21:18:00 GMT -5

1956

1956 was a year of contrasting fortunes, instant success for some, long-delayed success for others and a final success for one. The older generation still making great movies with a younger generation making small waves. Cinema attendance was rising with war films still popular, period dramas gaining credence, the younger Japanese generation were also getting noticed for different reasons.

Tokyo, 1956

Building on the success of “Floating Clouds” the year before, Mikio Naruse assembled three of the biggest female stars in his drama “Flowing”. A long established geisha house run by Isuzu Yamada struggles under debt, her daughter Hideko Takamine doesn’t believe in the geisha business thinking it has no future, the film shows what happens outside of serving customers, seen through the eyes of the new maid Kinuyo Tanaka. A well acted affair with two of the “seven samurai” providing cameos. Hideko Takamine (centre) facing Isuzu Yamada (right) The story of Japanese war criminals was considered too politically controversial by the censors (they didn’t want to upset the Americans), instead of heavy cuts Masaki Kobayashi decided to shelve the project, three years later “The Thick Walled Room” hit the screens. Taking place 4 years after the war, the story focuses on a group of low-level Japanese soldiers imprisoned as war criminals hoping for release. In flashbacks we learn more about the prisoners, one recalls being ordered by a superior to kill an innocent villager, at his trial the superior shirks responsibility for the order. The after-effects of the war aren’t simply psychological, the prisoners also discuss Japan’s future as a pacifist nation or a strongly militarised one to reject being “bossed around by outsiders”, a campaign to release low-level war criminals gains traction as the Korean War rages on and the term “commie” is considered taboo. Overall a good film by a director better known for his later war films.  The prisoners in their cell Taking another view of the war effort, “The Burmese Harp” was based on a children’s novel about Japanese soldiers in the Burma campaign, the harp-playing Mizushima goes missing near the end of the war, his comrades think a Buddhist monk resembles him but can’t be sure. Sentimental yet moving, it gave foreign audiences a view of Japan’s defeat it had not seen before, it was the first major hit for director Kon Ichikawa winning a special prize at Venice and bagging an Oscar nomination for “Best Foreign Film”. It was remade by the same director almost 30 years later. Away from the fields of war, a struggling young couple drift into Tokyo’s red light district looking for money and work. “Suzake Paradise: Red Light” was one of several films made that year by the prolific director Yuzo Kawashima, considered a bright spot in his late career. The young woman Tsutae was a former geisha girl trying to go straight, returning to that environment isn’t ideal but it’s better than moping around like her husband Yoshiji, who isn’t the “hustle to survive” type. Both are helped by the friendly bar owner Otoku, all-too aware of the dangers living and working in a place like this, she understands passers-by are reluctant to stick around long-term. Tsutae gets work in a bar, he gets a noodle delivery job, the plot complicates when Tsutae befriends a wealthy patron willing to rent an apartment for her, much to the disgust of Yoshiji. A decent film in a seedy setting, Yuzo Kawashima would score bigger success the following year. The end of the Samurai trilogy is a disjointed affair needing to tie up a lot of loose ends. Miyamoto Musashi has been challenged to a duel by the flamboyant and highly talented Sasaki Kojiro, Miyamoto agrees to the duel in a year’s time, seeking spiritual contentment in a simple life. The movie is most famous for the legendary final duel at Ganryu Island, on a beautiful beach at the magic hour. After his disappointing foray into colour films, Kenji Mizoguchi returned to a scene he was very familiar with in his younger days: the brothel. Early in his career he was suspended by the film studio after being attacked by a prostitute he was living with at the time, leaving scars on his back; Kenji would later remark “you can’t understand a woman until you’ve been stabbed by her”. The movie depicts the lives of 5 prostitutes working in a brothel as the Japanese Parliament considers outlawing prostitution. It turned out to be the final film of Kenji Mizoguchi’s career, dying from leukaemia at the age of 58 later that year. That same year another film aimed at younger audiences caused quite a stir, an adaptation of a novel by future Governor of Tokyo Shintaro Ishihara, whose older brother starred in the film. A story of two teenage brothers hanging out at a beachside resort. They smoke, drink, go clubbing, boating, the typical disaffected teenagers of wealthy parents with too much time and money for their own good. They both become attracted to the same girl and receive far more than they bargained for. Compared to all the other films that year, “Crazed Fruit” was far more Americanised than the rest, shocking older audiences at the time it’s often considered the first film of the Japanese New Wave, a fascinating time capsule and a potential harbinger of the future.

|

|

|

|

Post by andrew on Feb 5, 2021 5:12:13 GMT -5

I do hope you're planning to publish all this, at some point. I'd buy it.

|

|

|

|

Post by Woland on Feb 6, 2021 13:46:47 GMT -5

1957

1957 brought huge numbers of cinema-goers young and old to the theatres, a year known for a mixture of period dramas aimed at older audiences and gangster flicks for the younger demographic. In a time before television impacted cinemagoers, “Emperor Meiji and the Great Russo-Japanese War” sold a record-breaking 20 million admissions (still the 5th highest in Japanese box office history) and earned ¥ 542 million, the previous year’s highest grossing film managed ¥ 353 million. It would also see the growth of a not-so-new film studio challenging Shochiku and Toho.

Still from "Emperor Meiji".

In “Eight Hours of Terror” a landslide puts a train out of service among the mountains, a cross-section of Japanese society complaining about the “terrible Japanese railway service” have to take a rickety old bus across dangerous mountain roads to catch their connection to Tokyo. Among the passengers are a businessman and his arrogant wife, a lingerie salesman, a couple radical students, an aspiring actress, a sex worker, a single mother with her sick baby. Adding to their fears are a handcuffed murderer escorted by a police officer and news of two bank robbers on the run. Loosely based on the John Ford western “Stagecoach”, it was the 5th film by the infamous director Seijun Suzuki. Compared to some of his later flicks it’s quite tame and straightforward, some of the humour falls flat, its strong points revolve around the "bad" characters showing off their good side to the surprise of some judgemental passengers.  Most of the passengers aboard the rickety bus Over the course of the 50s jidaigeki became more popular with Japanese audiences, gone were the mild ties to militarism replaced by cinematic spectacle, giant sets and lavish costumes. In 1957 Akira Kurosawa had already adapted Maxim Gorky’s play “Lower Depths”, he had the chance to complete a pet project he’d wanted to make since “Rashomon”, upon learning of Orson Welles’ version of Macbeth in 1948 he waited until the time was right. “Throne of Blood” turns Medieval Scotland into Feudal Japan, Spider Web Castle is heavily fortified and perennially shrouded in mist, doubly protected by the nearby forest with its labyrinthine trails confusing all potential enemies. Two generals and best friends Washizu (Toshiro Mifune) and Miki (Minoru Chiaki) get lost in the forest after winning a battle, an evil spirit foretells their future, thus setting in motion Washizu/Macbeth’s bloody rise and fall, egged on by his scheming wife Asaji (Isuzu Yamada). One of the better adaptations of Shakespeare’s play, the weather is the true star of the show, lighting and mist, wind and rain add to the films ominous atmosphere with ghostly apparitions enhanced by the high contrast photography. Some scenes drag on too long while Mifune’s descent into madness brings out his overacting side, still a moody film with a memorable ending which gave Mifune recurring nightmares. While the Kurosawa-Mifune partnership prospered, the Kobayashi-Nakadai partnership was just getting started in “Black River”. Nishida (Fumio Watanabe) is a good student looking to save on money in the middle of a depression. He rents a room in a dilapidated flat with all the other residents using every available trick to avoid paying rent, all of them resent the American Military base nearby yet they feed off the illicit shadow economy keeping them afloat. Nishida has feelings for a kind-hearted student Shizuko (Ineko Arima) but she gets roped into the world of Joe the Killer (Tatsuya Nakadai), a petty gangster always seen in shades and white blazer, feared and respected by everyone. A sordid love-triangle with a jazzy soundtrack and noirish cinematography, Shochiku’s young noir flick looks a little more polished compared to their rivals at Nikkatsu, Tatsuya Nakadai makes a convincing psychopath while Ineko Arima proves she’s tougher than she looks. Another solid film from Masaki Kobayashi on the cusp of his and Nakadai’s major breakthrough. A gritty if at times contrived noir flick, a man called Joji (Yujiro Ishihara) finds trouble in the form of a lonely woman called Seiko (Mie Kitahara) by the docks. She’s a cabaret singer who thinks she killed a man, he helps her lie low at his restaurant until the newspapers confirm whether there was a murder or not. As the two become close they slowly reveal their dark pasts: she used to sing opera until her vocal cords couldn’t take it, he was a prized welterweight until he killed a man in a bar-room brawl. He’s secretly hoping to join his brother in Brazil, a dwindling dream which drives the second half of the story. Rough around the edges with some visual flair at times, it reunites the duo from “Crazed Fruit” one year earlier with debutante (sole) director Koreyoshi Kurahara. It becomes less interesting in the second half even if the final confrontation has its moments, in some respects it’s a bad film yet its interesting shots and themes still make it worth a look. Snow capped mountains provide the backdrop for this adaptation of the Yasunari Kawabata novel, a relationship develops between the outmoded artist Shimamura and a geisha called Komako. She’s financially tied to her foster family and engaged to their son Yukio, dying from consumption. Yukio’s sister resents Komako, who sees Shimamura as her ticket to a better life. There’s references to the failed military coup of the 1930s yet this barely affects the plot. It looks slick and polished yet it remains oddly unsatisfying, Kawabata’s novel is so short you could probably finish it faster than this 2 hour film adaptation.  Ryo Ikebe and Keiko Kishi in the snow Yasuzo Masumura was assistant director on Kenji Mizoguchi’s final three films, in his directorial debut he follows two youngsters who meet in prison: Kinichi (Hiroshi Kawaguchi) forms a bond with Akiko (Hitomi Nozoe), both need 100,000 yen to release their fathers from prison. She’s lonely and he’s insensitive, his mother is cold while hers suffers from TB. An interesting look at disaffected youth, what it lacks in plot it makes up with understated style and charm. A real contrast to Masumura’s later career.  Kinichi and Akiko bonding.

After the release of “Tokyo Story” Yasujiro Ozu had a lean period in films; in 1955 he wrote the screenplay for Kinuyo Tanaka’s film “The Moon has Risen”, one year later he started pre-production on “Early Spring”. In the 3 years between those films studios feared Ozu’s brand of family drama was outdated, from this point on Ozu would cast younger actors in his films, playing graduates heading into the stultifying life of a white collar worker. In 1957 he reunited Chishu Ryu and Setsuko Hara in a darker tone, he plays the judgemental patriarch Shukichi with two daughters; Takako (Setsuko Hara) is trapped in an unhappy marriage, she’s returned to her father’s home with her little girl, Akiko (Ineko Arima) is a college student with an unloving boyfriend. The plot thickens when the owner of a mahjong parlour called Kisako (Isuzu Yamada) seems to know an awful lot about the family, turns out she’s their long-lost mother. One of Ozu’s bleakest and longest films at 2 hours 20 minutes, it was also his final black-and-white film. A lighthouse keeper Shiro (Keiji Sada) returns from his father’s funeral with a new wife Kiyoko (Hideko Takamine), Japan has gone to war in Shanghai. The timeline tracks the war and aftermath through the eyes of the young couple, moving between lighthouses all over Japan, supported by a couple friends and fellow workers. A critical and commercial success upon release, the story was taken from a magazine article written by the wife of a lighthouse keeper, it’s a long, sentimental flick suffering in comparison to the earlier Takamine-Kinoshita collaboration “Twenty Four Eyes”. The supporting cast including their children Kotaro and Yukino aren’t fleshed out, the emotional pull of the final third isn’t as strong as it could’ve been thanks to the hurried gaps between time periods; it almost rushes through the war period. At 160 minutes you’ll appreciate the isolated beauty of Japan’s coastal regions and small islands, it’s not enough to make this film worthwhile.  Keiji Sada and Hideko Takamine as an old couple near the end of the film Hideko Takamine plays the strong, confident independent Shima in Taisho-era Japan, mistreated by men who can’t control her and looked down on for her non-conformism. Naruse’s episodic story follows her as she fights with her first husband and miscarriages, takes a lover to repay debts at a hot spring resort (she will never be anyone’s concubine). Later she becomes the only woman at a sewing factory, always looking to move up professionally even when her second husband is happy to take things slow. Despite dragging in places it’s one of the better “plight of women” stories by Mikio Naruse, Hideko gets to show off her acting range as an assertive woman getting into more fights than expected (with men and women). In the final third a young Tatsuya Nakadai gets an important small role, one of 5 films he made with Mikio Naruse. Shima giving her second husband a cold, hard lesson

At the start of the movie a voiceover shows us the Shinagawa red-light district soon to be closed thanks to government legislature, the story switches from the modern to the Bakumatsu era (the final years before the Meiji restoration). The Sagami inn houses several characters all with their own story: two competing geishas Koharu and Osome get into a catfight over the number 1 slot, a series of marriage proposals and an attempted double suicide show the lengths they’ll take to become number one; a group of penniless nationalist samurai plot to blow up the nearby Foreigners Quarters (a humiliating treaty is mentioned), shouting their plans loud enough for the entire neighbourhood to hear. Ohisa works in the kitchen until her father gambles so much he sells her into the brothel, the owners’ son Tokusaburo spends too much time and money in brothels and doesn’t pay back. The “hero” of the tale is Saheji, a witty and resourceful grifter first loathed by the owners for partying with friends and never paying, yet through cunning tricks and set pieces manages to stay 3 steps ahead of everyone else, solving all their problems and getting paid to do so. By the end of the film we discover he’s not so perfect, by then we’ve become so entertained by his antics you just can’t help but love him.  Saheji (Frankie Sakai) and nationalist samurai Takasugi (Yujiro Ishihara), the latter based on a real samurai and important figure in the Meiji Restoration

Voted 4th greatest Japanese film of all time by Kinema Junpo magazine, it’s a period piece with obvious parallels to the present, an ensemble comedy that needs a couple viewings to work out all the different characters. With foreign comedies you expect some humour lost in subtitles, “Sun-Tribe” has enough physical humour and absurd situations with a bit of bawdiness thrown in: one bookseller trades mainly in stories about “love suicides”, a couple’s prayers to Buddha are drowned out by a foreign military parade (with bagpipes) outside, one servant is threatened with being sold to a male brothel if Saheji doesn’t pay up, another geisha has to contend with an eye infection and her baby, at one point the nationalist samurai all go for a “group piss”. Nikkatsu studios churned out lots of contemporary crime flicks in 1957 but their best film of the year showed the youngsters satirising the older period dramas with a modern twist. |

|

|

|

Post by Woland on Feb 10, 2021 15:34:11 GMT -5

I do hope you're planning to publish all this, at some point. I'd buy it.

My first intention for this series was a test of where I am writing-wise, I used to write movie reviews a long time ago but it's such a competitive field and world cinema is a niche topic, writing is hard enough to make a living from. It's been a fun project so far though I'm hardly an expert on Japanese cinema; Donald Richie lived and worked in Japan for decades writing numerous books on Japanese culture and films, his book "100 Years of Japanese Cinema" is a very good introduction despite its age, I've stolen from /been influenced by it in writing this series.

Since I can't shoehorn it into the timeline here's a lengthy interview with Akira Kurosawa from 1993, a couple months after his final film "Madadayo" was released. It's a wide-ranging conversation going through Kurosawa's personal life and career, some of his movies, his filmmaking process and his view of the Japanese film industry. Keep in mind the interviewer Nagisa Oshima was a famous director ("Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence", "In the Realm of the Senses) who once said "my hatred of Japanese cinema includes absolutely all of it".

|

|

![]()

![]()