Post by Aurelia on Jun 3, 2020 11:04:40 GMT -5

RED

On the farthest edge of color waves visible to humans, there is red.

It evokes a range of complex meanings and ideas: love, anger, risk all come to mind upon glimpsing it. Over the course of history, it's become a symbol for concepts both real and abstract. It is used to represent sacrifice, luxury, passion, and victory - though darker meanings are also affixed to red, namely authority, war, desire, guilt and evil. An Egyptian prayer from around 1700 B.C. reads: "O Isis... deliver me, set me free from all bad, evil red things!"

Red is splashed across our consciousness, taking forms of the highest good and greatest evil.

It is difficult to feel indifferent about red. Red commands the eye.

For a large portion of history, this shade was as elusive to produce as it was coveted. Herbs and minerals often produced what is called "fugitive colors" - meaning that their original tones soon faded or washed out into pale pinks and browns. The coveted shade was True Red - a "primary" color; a vivid crimson; the same color that flowed from an opened vein.

This gallery is an exploration of the quest for red, it's use throughout history and it's impact on modern viewers.

Detail: Cueva de las Manos, Argentina. Paintings carbon dated to 7300 B.C.

Many of humanity's first attempts to attain red have been lost to time, but one of the earliest brick-toned pigments used has remained untouched by light or weather for over 285,000 years. When Paleolithic peoples recognized the lasting qualities of red ochre, a natural clay pigment made from iron oxides (hematite), they utilized them extensively to blanket graves with color, decorate and adorn their skin and create vivid images on cave walls. At Cueva de las Manos, in Argentina, red ochre clay was liquefied, held in the mouth and expelled through specially made bone straws that aerated the pigment, creating a fine spray of color. It essentially worked like a stencil, using the hand as a resist and the cave wall as a canvas.

Depending of on the geographic location of the the ochre, it's colors ranged from yellow to purple to red. Heating of ochre would darken it's tone to a deep, dark red, creating what is perhaps one of the reds used longest throughout history. The ancient Egyptians used red ochre to designate men from women in their renderings - the color was used extensively through the Renaissance with raw hematite-laden chalks dug out if the ground, sharpened and used for sketching. By the 19th century, iron oxides were being artificially formulated in laboratories, creating Mars red.

The Villa of the Mysteries - scenes of initiation rites into the Bacchic Mystery Cult.

One of the truest, brightest and lasting reds available in the ancient world was produced from cinnabar. This pigment, called vermilion, was produced by finely grinding mineral mercuric sulfide - it was favored by the Romans, who sent prisoners and slaves to their death, working the toxic mines of Almaden. Cinnabar was an indicator of wealth, and as demand rose it's price had to be controlled by the Roman government to keep it from becoming impossibly expensive.

Examples of decadent use of red can be seen in the frescoes in the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii. Working with such precious materials proved to be too tempting to resist, as Pliny the Elder describes; and by frequently washing their brushes in water they later secreted away, the fresco artists of the Villa of the Mysteries stole a substantial cache of red.

"Nothing is more carefully guarded. It is forbidden to break up or refine the cinnabar on the spot. They send it to Rome in its natural condition, under seal, to the extent of some ten thousand pounds a year. The sales price is fixed by law to keep it from becoming impossibly expensive, and the price fixed is seventy sesterces a pound." - Pliny the Elder.

Ancient authors referred to the pigment created from cinnabar as vermilion - but prior to the Middle Ages, the Chinese formulated a synthetic shade that was also called vermilion (Chinese Vermilion). The orange-tinged red of Chinese vermilion had one drawback: it was a fugitive pigment. It was prone to deterioration as exposure to sunlight caused it to darken to black, whereas true cinnabar vermilion remained permanently bright, most vibrant of reds.

In Asian culture, red is one of the most auspicious of colors, where is symbolized joy, good fortune and was also believed to have the power to ward off evil. The use of red seals to sign art and designate ownership of art started during the Shang Dynasty (1600 to 1049 BC) - the seal paste (zhūshā) was almost always exclusively red.

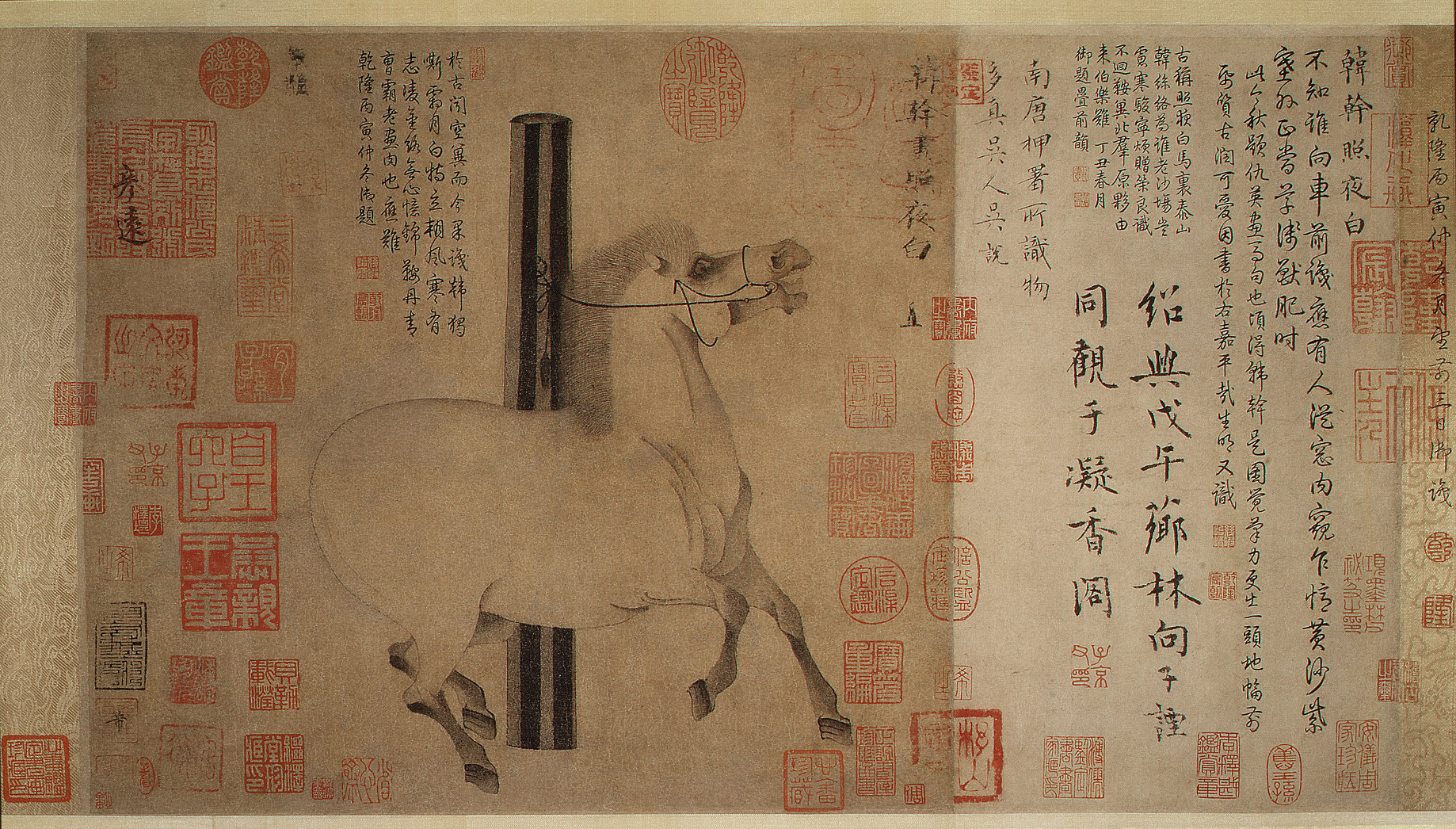

Night-Shining White - Han Gan

Han Gan's portrait of Night-Shining White, a charger belonging to Emperor Xuanzong (r. 712–56) is covered in over one thousand vermilion-hued seals, indicating it's importance and long-running impact of what may be the greatest equine portrait in Chinese painting. The number of red seals greatly elevated the value - as well as the virtue - of the art they adorned. The horse itself was one of the "Celestial horses" was was prized for it's characteristic red, blood-drenched sweat upon exertion - they were believed to be dragons in disguise, bringers of wealth and luck.

One of many organic reds used antiquity was derived from the roots of the Madder plant (rubia tintorum). Scraps of madder dyed fabrics have been found in the tomb of the pharaoh, Tutankhamun - it was also widely used by the Greeks and Romans. By the 13th century, madder was being cultivated on a fairly large scale across Europe - all in the pursuit of the perfect scarlet hue.

The Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele - Jan van Eyck

This same purple-tinged red dye was later "laked" through the addition of potash alum, creating madder lake. Though it is derived from an organic dye, madder is one of the more stable of the natural pigments - and it's unique, transparent qualities made it indispensable to painters in the Renaissance and Baroque periods. X-radiograph images of van Eyck's paintings reveal the manner in which the artist layered three coats of transparent madder lake over other reds, achieving depth and adding to the 3-dimensional quality of his fabric draperies and enhancing the richness of their tones

Under magnification - layers of kermes lake and madder lake over white chalk - Jan van Eyck

Detail -The Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele - Jan van Eyck

One of the first synthetic red pigments was produced by the Romans, who took white lead and heated it to high temperatures, making minium, also called red lead. Producing minium was highly toxic - carelessly handling its powdered form could result in death. While the pigment had fugitive qualities and tended to fade to white with light exposure, it created an inexpensive, vivid hue. It favored by medieval illustrators in manuscript illuminations (which is no surprise, seeing as vermilion cost the same as gold leaf at the time) and Mughal artists of the 17th and 18th centuries. Red lead was also used by artists in the 1800's - including Vincent van Gogh.

"Painting it was hard graft... in addition red, yellow, brown ochre, black, terra sienna, bistre, and the result is a red-brown that varies from bistre to deep wine-red and to pale, blond reddish... " - Vincent van Gogh

Self Portrait with Bandaged Ear and Pipe - Vincent van Gogh

Van Gogh understood the symbolic power of colors, using them to express the emotions that brimmed within him - often he used red lead paired it with it's color contrast, green. The blood red hue of minium added tension to his radiant palette, as the artist loaded his paintings with suggestion: "I tried to express through red and green the terrible passions of humanity." Van Gogh's treating physician, Dr. Peyron, described the artist eating his lead-based (red minium) paint in an attempt to poison himself - the very characteristic scintillation and halos of natural and artificial light seen in his paintings may have been a result of swelling of the retinas due to lead poisoning which caused van Gogh to see glare from light sources.

Crimson red was another blood red pigment used since ancient times, harvested from the dried insect, Kermes vermilio. Crushing the scale beetles would result in a rich orangey-red stain; it was called the "King's Red" as it surpassed Tyrian purple in both it's cost and prestige. The kermes or crimson red was colorfast when used to dye wool and silk and was used exclusively in the medieval European manufacture of "Scarlet" (a finely woven woolen luxury cloth dyed in red).

Portrait of Agostino Pallavicini - Anthony van Dyck

The desiccated insects closely resembled grains, which is why they were referred to as "grain" in most Western European languages. Red was the chosen color worn by royalty and cardinals; judges and executioners - the shade was an exclusive rite of nobility (as dictated by English Sumptuary Laws, but also by it's costliness to own). Van Dyck's portrait of Agostino Pallavicini, the ambassador to the Pope, displays the flowing, luxuriant red cloth associated with his rank. The hue was worn very consciously, as blood red symbolized life and death, martyrdom, forgiveness (evoking the concept of Christ's atoning blood), as well as power over all over these concepts.

"Item for making of one peire of bodies of crymsen satin

Item for making two pairs of bodies for petticoats of crymsen satin

Item for making a pair of bodies for a Verthingall of crymsen Grosgrain..." - from the Clothing Warrants of Mary Tudor

Item for making two pairs of bodies for petticoats of crymsen satin

Item for making a pair of bodies for a Verthingall of crymsen Grosgrain..." - from the Clothing Warrants of Mary Tudor

It wasn't until the introduction of the cochineal (Dactylopius coccus) beetle to Europeans following the Spanish Expedition of South America in 1518, that artists and dyers found the key to the most vivid shades: Carmine red. The kermes could produce a single orangey crimson - but by altering the processes in which they heated the dried cochineal beetles, they could create a range of shades: from scarlets and deep burgundies; to blood-like blue-reds; to gentle, yet lasting blush tones. In addition to the sheer array of stains it made possible, cochineal beetles were more potent in their colorful qualities than kermes - only a tenth of the weight was required to make the same amount of pigment. Very quickly, the European appetite for this American "red gold" was whetted, and by 1600, the Spanish had exported somewhere between 250,000 and 300,000 pounds of cochineal beetles. By the 18th century, it was exported as far and wide; carmine red began to turn up in all sorts of more "ordinary" places.

Carmine satin high white leather Louis heel shoes - England - 1775-1785

For a large portion of the 17th and 18th centuries it was all the rage for both men and women to own carmine red shoes. Louis XIV had limited the wearing of le Talons Rouge to himself and his court, but in the century after his death, the availability and lust for red soon meant that more lowly types were wearing them. The British Army - known to the Americans during the Revolution as "Red Coats" - had their distinctively vivid uniforms dyed with carmine. Many artists also used carmine lake, a pigment harvested from dye-laden scraps of fabric or from the beetle itself, in translucent glazes over renderings of draperies or to add life-like color to skin tones. Sir Joshua Reynolds used carmine lake extensively in his portraiture - though as years passed, this fugitive pigment would fade; the result made the sitters appear to be carved from marble.

When Sr Joshua Reynolds died

All nature was degraded;

The King dropped a tear into the Queen’s ear;

And all his Pictures Faded.

- William Blake

All nature was degraded;

The King dropped a tear into the Queen’s ear;

And all his Pictures Faded.

- William Blake

Portrait of John Burgoyne - Joshua Reynolds

Here you can see the vividness of the military uniform (that in Reynold's day would have been dyed in carmine and was most likely painted using synthetic red ochre) remains, as it was likely painted using vermilion; but the flesh tones are colorlessly wan, as the rosy glazes used to tint the under-painting have faded completely. While Joshua Reynolds was the champion of experimenting with new pigments and techniques, modern viewers are ultimately robbed of the life-like sensation of his faded works. Many other groundbreaking artists would have their artistry undone by their testing new red mediums.

The 19th century saw a synthetic version of an ancient mineral make it's way to artists' palettes - chemist-created iron oxides, called Mars red, after the alchemical name for metallic element iron. Mars red was an opaque, brick-tinged red that embodied all of the strengths and permanency of it's natural counterpart - withstanding exposure to light without loss of tone. It was a favorite of British artists, including John Martin.

Pandæmonium - John Martin

The rich red shades used in many of his fantastically apocalyptic paintings, were often symbolic of spiritual evil - a malevolent reputation red has had for eras. The mythos of the medieval bestiaries drew their inspiration from Pliny concerning the procurement of an evil red pigment. The recipe for red pigment described that the dragon's belly is fully of fire and blood, and that by rupturing his skin, this sanguine shade could be collected by artists. This color was corrupt by nature and was only used specifically for the most vile of renderings: the face of Lucifer, the fires of hell and the punishment of the wicked. While a laboratory is a far cry from the insides of a dragon, the synthetic production of Mars red brought life in the work of Martin, reinforcing the split role that red plays in all our darkest imaginings.

When a German chemist discovered a new colorant in 1817, cadmium red was thought to be the "modern" answer for the dangerous vermilion (cinnabar) that had been in use for thousands of years. Today, we know that cadmium red is also highly toxic formulation of true red, but for artists working with vermilion, something as simple as a cut on the hand or smoking while painting could result in the artist being poisoned. Cadmium red offered a "safer" alternative.

L'Atelier Rouge - Henri Matisse

When heated with selenium, cadmium darkens to a rich tint - it's foremost strengths being it's opacity and good lightfastness. The only problem with producing cadmium red was locating enough of the rare, metal sulfite mineral greenochite to be produced into the pigment. The scarcity made the red rather costly, meaning that generally artists with more financial means used the color most freely. Cadmium red was a favorite of Matisse, who tried without luck to convert this friend Renoir to cadmium from vermilion. An oldest son from a wealthy family, the extravagant use of the shade reveals that while the paint was costly, Matisse was not the average impoverished artist. It must also be said that Henri Matisse used cadmium red to it's fullest potential - using it's thick, opaque qualities to tone entire canvases, toying with the viewer's sense of perspective.

"A certain blue enters your soul. A certain red has an effect on your blood-pressure." - Henri Matisse

More modern artists have turned to newer, less fusty sources for their saturated reds - including a synthetic pigment called lithol red. Patented at the end of the 1800's, lithol red was a cheap, vibrant ink used almost exclusively in industrial paint and printing applications. Artists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko experimented with commercial house paints - following a trend seen in mid-20th century that saw artists trying new, untested mediums.

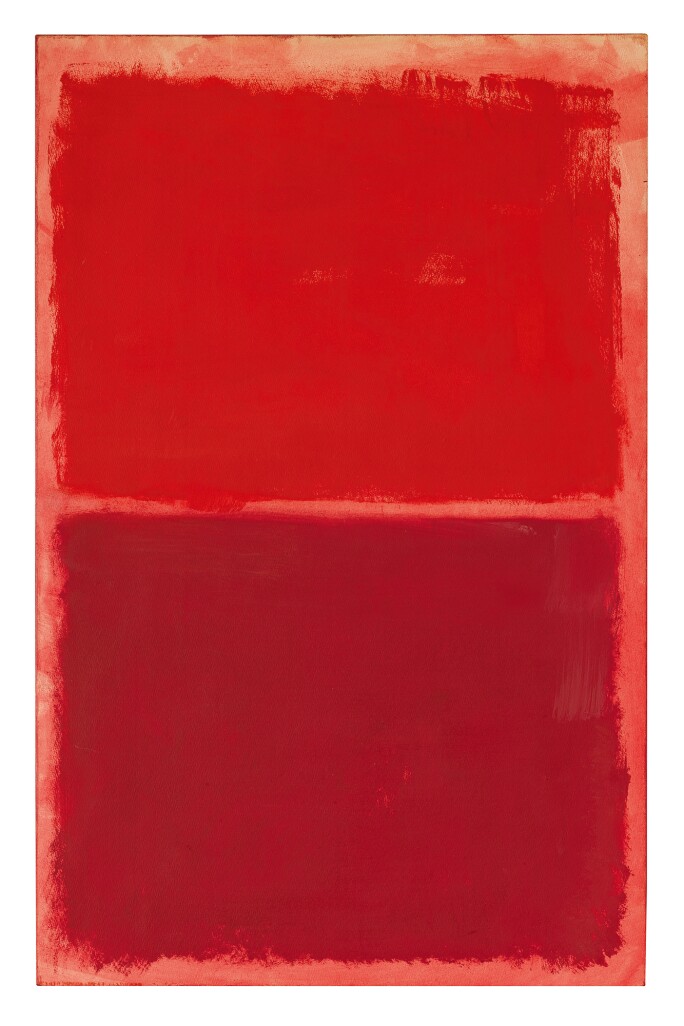

Untitled - Red on Red - Mark Rothko

Mark Rothko used lithol red extensively in his late period paintings where massive canvas sizes were stained with the intoxicating bright, clean colors. Rothko used lithol red to cover vast areas in expressive, awe-inspiring sweeps of color. The one disadvantage to Rothko's pigment of choice is that lithol red is fugitive - it is highly sensitive to light exposure, which makes it to fade to blue. The resulting shift causes the emotive qualities of Rothko's paintings to be sapped over the course of a few decades - which in turn causes a new sense of urgency for collectors and museums to protect the original integrity of the pieces.

“There is only one thing I fear in life, my friend… One day the black will swallow the red.” - Mark Rothko

The sense of loosing the vibrancy of red is cause for concern for contemporary art viewers, as we would all like to see the world as vividly as artists in the past have portrayed it. By studying the qualities of fugitive pigments, art conservationists work to take immediate action to preserve the potency of the images we treasure - that the sense of joy or evil, passion or chaos embroiled in the picture plane may not be lost completely. It was not difficult to see why artists are drawn to the complex emotional content of true red, just as we ourselves are captivated by it in turn. In truth our valuation of red is much like that of ancient peoples - we seek it's permanence, that generations to come may admire humanity's favorite hue.